In many cases, Chinese brush splitting happens because users don’t know how to adjust the brush tip properly. Today’s article focuses on this issue and explores proper brush adjustment techniques. I was inspired to write this after receiving a negative review at Qi Ming Wen Fang.

Why Write Another Article About Chinese Brush Splitting?

I’ve already discussed the story behind Qi Ming Wen Fang’s first negative review on Taobao in my article about brush sizes. For this second negative review, I immediately contacted the buyer online, hoping to exchange a new brush for them in return for a better rating. I also called, but they didn’t answer – probably because it was an unknown number. I’m not sure if they’ll contact me so I can provide after-sales service. I’m still waiting to hear from them.

Regardless, I need to write this article specifically about Chinese brush splitting. To put it more meaningfully, this article isn’t just for myself – it’s also for all the fellow sellers who put their heart into making or selling brushes.

There are several other reasons for writing this article. First, the buyer might be a beginner who doesn’t understand how to identify actual brush splitting. Second, they might be using the brush incorrectly – for example, using a small brush to write large characters, which causes splitting. Third, my brush might genuinely have a quality issue, making them too upset to communicate with me. Fourth, many calligraphy enthusiasts might not fully understand what brush splitting really is, or how to avoid reasonable splitting through proper brush adjustment. Nobody has explained to them what counts as splitting, what kind of splitting is normal, and what kind indicates a quality problem.

Related Reading:

The Real Cause: Poor Brush Adjustment Techniques

In my view, setting other reasons aside, many beginners who report brush splitting issues are likely not paying attention to brush adjustment, while focusing too much on whether the brush tip stays pointed.

In other words, during normal writing, each hair in the brush head undergoes physical deformation, but the writer doesn’t correct or adjust the brush tip in time.

Related Reading:

- Teacher Liang Sanri’s Lecture on Brush Adjustment – Qi Ming Notes (Part 1)

- Teacher Liang Sanri’s Lecture on Brush Adjustment – Qi Ming Notes (Part 2)

In fact, people who report brush splitting issues at Qi Ming Wen Fang are usually beginners. They pay special attention to whether the brush tip still maintains a good point after finishing a stroke, as described by the seller. Their attention focuses on whether the front of the brush head remains sharp.

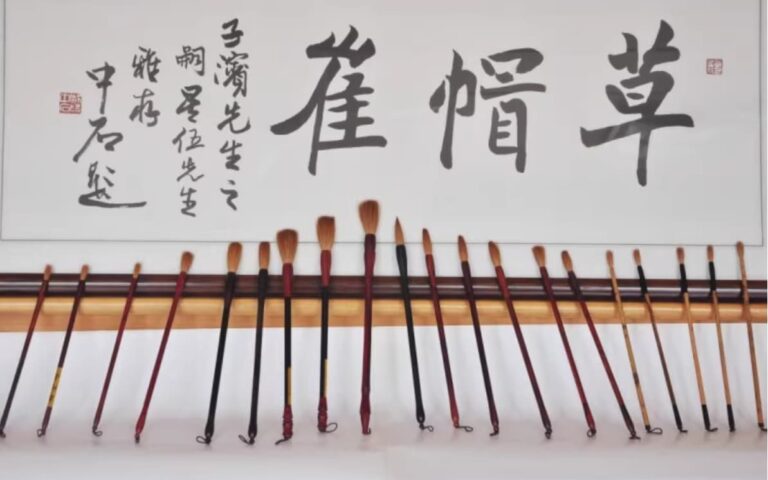

Now, let’s look at an image.

This is a brush position diagram that I referenced in my previous article “What is the ‘One-Third Brush’ Technique? Why Does Understanding It Mean Understanding Brush Movement?”

Typically, we only use the front half of a Chinese brush head. Within this front half, we use different positions depending on the character size or calligraphy style – this is called the “one-third brush” technique.

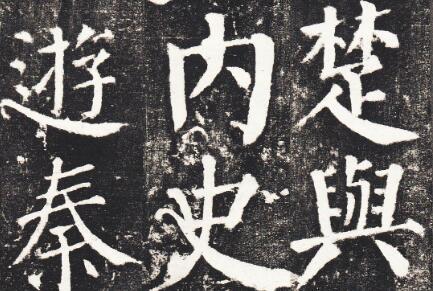

For example, many strokes in Yan Zhenqing’s style are quite thick, frequently requiring the full one-third of the brush. (This is why Qi Ming Wen Fang asks customers about their calligraphy style – for characters of the same size, Yan style requires a larger brush because the strokes are thicker and bolder.)

Chu Suiliang’s style, on the other hand, features thinner and more dynamic strokes, so it uses the one-third technique less frequently.

Of course, it’s possible that Yan Zhenqing simply used a larger brush than Chu Suiliang, so he was actually only using one-third of his brush too.

However, as far as I know, chicken-leg brushes were very popular during the Tang Dynasty and even early Song Dynasty (see my previous article “How Ancient Chinese Brushes Were Made and Materials?“). Brush head sizes didn’t vary as much as they do today.

Understanding “Small Brush, Large Characters”

So, what many beginners call “splitting” is very likely caused by using a small brush to write large characters, or by focusing too much on deformation while neglecting brush adjustment.

Let’s talk about using small brushes for large characters first. For example, if you use Qi Ming Wen Fang’s Qingquan large-size brush to write Yan-style characters around 15 centimeters tall, splitting will be hard to avoid. And the splitting will be quite severe.

In reality, the Qingquan large-size brush works best for characters up to about 10 centimeters. Some calligraphy enthusiasts have even told me that the Qingquan large-size works best for 7-8 centimeter characters, while others prefer even smaller sizes. This varies from person to person. As long as it helps your hand and mind work smoothly together, it’s fine. Generally speaking, large brushes can write small characters, but small brushes shouldn’t write large characters – or should do so sparingly.

Frequently using more than one-third of the brush, or wearing down the middle and upper parts of the brush head through contact with paper, may weaken the brush’s core strength. However, sometimes you need to use it more and wear it down to find that sweet spot where you think, “Ah, after about ten uses, the core strength feels just right.”

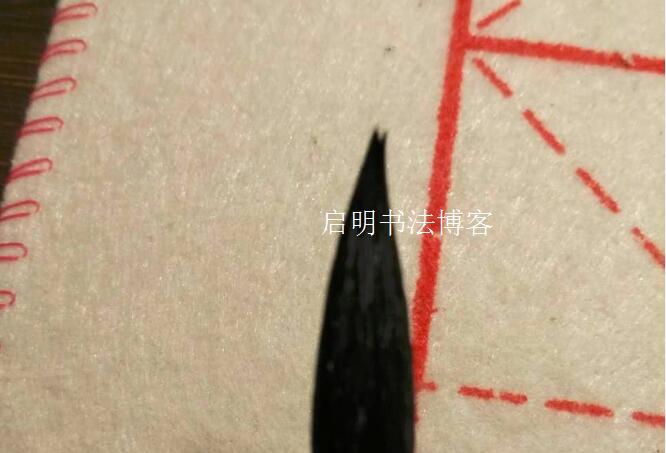

When you use two-thirds or the full one-third of the brush, deformation like shown above easily occurs. Many calligraphy beginners see the brush tip not staying together and conclude that the brush quality is terrible – “It splits after just one stroke!” Then they quietly go to Taobao to leave a negative review, seriously attaching a photo. Yes, they’re that frustrated yet responsible, warning future buyers.

Actually, this kind of minor splitting can be completely fixed by dipping in ink and reshaping the brush. I explained this in my article “What is Chinese Brush Splitting and What Should You Do About It?“

You can also adjust the brush mid-air or on paper.

The Natural Adjustment Process

For example, when testing Qi Ming Wen Fang’s Qingyin dou brush, I wrote the character “Fu” (福). Notice the beginning of the left vertical stroke in the lower “Tian” (田) section – the circled area. You can see from the image that I started this stroke directly with a “split” brush. The stroke goes from thin to thick, and correspondingly, the brush hair touching the paper gradually increases. As the stroke gets thicker, the brush hairs spread wider – at this point, the brush is already “split.” If you don’t believe me, stop and lift the brush to look.

However, I didn’t stop to worry about the split brush tip. Instead, I immediately wrote the second stroke – the horizontal line.

Look at the beginning point in the rectangular box – it’s very sharp. Logically, after finishing the first vertical stroke, the brush head should be “split,” and the second stroke should start with an uneven effect like the first vertical stroke. So why is the beginning of the second stroke so sharp? Why does the brush’s “pointing” effect work so well?

Actually, during this process, I didn’t dip in ink or reshape the brush to correct the tip. I simply naturally – or habitually – rotated the brush handle slightly or adjusted the angle at which the brush tip touched the paper.

For example, in this image of a paint brush, when I paint the first stroke horizontally, then rotate the brush 90 degrees for the second stroke, the painted area becomes much smaller. This “much smaller” area helps us create very sharp, exposed-tip strokes.

In my recent article – “Notes from Teacher Liang Sanri’s Lecture on Brush Nature and Brush Techniques” – a reverse-tip technique is repeatedly mentioned. I think if you read that article, you’ll understand brush techniques more deeply and thoroughly, rather than constantly focusing on how to adjust the brush tip to be perfectly pointed and sharp before each stroke.

Sometimes you need to complete this reverse-tip movement the moment you touch the paper. Other times, you complete the brush adjustment mid-air or before touching paper – for example, by twisting the handle.

What Actually Counts as Splitting?

So, what situations actually count as splitting? How do people view and handle it?

Here are some perspectives from calligraphy enthusiasts after I posted about brush splitting on social media:

Calligrapher A: From a writing perspective, using a small brush for large characters will cause tip splitting. Pressing too hard or holding down too long, or moving the brush without adjusting the tip, can also cause splitting. After dipping in ink once, writing several characters in succession can easily split the tip. You need to constantly adjust the tip while writing to maintain centered brush movement – this requires considerable skill. Of course, flying white and silk-thread effects from dry brush writing should happen naturally and don’t count as brush splitting.

Calligrapher B: There’s no need to worry about the brush not bouncing back and closing on its own. First, you need to control it yourself. Second, you need to adjust it yourself. This will improve your brush control. When I watch some calligraphers and teachers write, they rarely deliberately adjust the brush tip. It adjusts back, intentionally or unintentionally, when writing the next character or dipping in ink. They can find the angle needed for the next stroke – this requires quite high brush mastery.

Calligrapher C: Unless the quality is very poor or the brush belly and tip are uncoordinated, splitting generally won’t occur. Splitting is mostly caused by not knowing how to adjust the tip.

Calligrapher D: People who ask this question are usually beginners. When writing, you need to adjust the tip during stroke turns and endings. Learning to adjust the tip prevents so-called splitting. Most of the time, it’s not the brush’s fault.

Calligrapher E: I think this phenomenon mainly comes from spreading the brush hairs too much or not handling the return stroke properly. It has little to do with the brush and happens often. There’s no need to reshape the brush. My teacher said that after dipping in ink, try to write multiple characters without constantly reshaping – otherwise, the brush intention becomes choppy and complicated. The tip needs constant adjustment within the strokes, so it’s adjusted for the next stroke. True splitting is different – splitting means the hairs at the brush belly or even root separate, making it impossible to point properly. When writing, you get double lines from one stroke, rough corners on square strokes – basically unusable. This usually results from improper cleaning, improper use, or external damage. Splitting is fatal damage to a brush. Even if you use online rescue methods, there will still be aftereffects. Even if there aren’t, it feels weird psychologically. Just my humble opinion.

Words of Wisdom from an Expert

Finally, I’ll quote a teacher’s advice on brush technique:

If your brush is too stiff, don’t write too fast. If it’s too soft, don’t write too slow. If it has a good point, pursue refinement. If it lacks a point, use round, contained movements. If it splits easily, use shallow strokes and more rotation. If it doesn’t split easily, you can press deep with varied pressure. In short, don’t make unrealistic demands on the brush’s performance – push it too hard and it will push back. Highlight the brush’s strengths and hide its weaknesses.

Addressing Customer Concerns

After saying all this, as a customer, you might still complain:

“Well, you’ve written a lot, so you can adjust naturally! You can habitually adjust the brush tip correctly – you’re experienced! But I’m a beginner! I don’t know how to adjust! I find all this adjusting annoying! Dipping and reshaping is annoying!”

“Didn’t you say in your article ‘What Makes a Good Chinese Brush?’ that a good brush should work well for both beginners and advanced calligraphers?! I’m a beginner! And I just don’t think it writes well!”

“Your brush is poor quality! I paid money for your brush, and you give me this!”

“What?! You cover return shipping if I return it – so what?! Returns are a hassle!”

“Why didn’t you carefully select one for me?! Why didn’t you break in the brush and test it in various situations to ensure it writes well before sending it to me?”

Honestly, today’s industrial and technological levels are very advanced, but Chinese brushes, as traditional writing tools, still cannot be mass-produced mechanically. They can only be handmade.

Those who’ve watched “Huang Jian’s Basic Calligraphy Course” probably heard Teacher Huang Jian say that even the most skilled master craftsmen can’t ensure every brush is identical. Although Qi Ming randomly inspects and tests each batch of brushes, I cannot break in and test every single brush before stocking it.

So Qi Ming Wen Fang can only guarantee that if you’re unsatisfied for any reason, you can return it anytime for a refund – even if you’ve dipped it in ink, we cover the return shipping.

Therefore, when you receive your brush, if you have any dissatisfaction or questions during use, please contact me immediately. I will take full responsibility and do my utmost to satisfy you – in fact, until you are satisfied.

A Final Word on Communication

If you’re willful and proud, refusing to communicate or contact Qi Ming at all – not even giving us a chance for that “one word” before we “part ways” – then all I can do is contact you promptly after discovering your negative review.

If I reach out to you proactively and you still refuse to communicate, then I can only quietly add you to my blacklist. This means my relationship with you and my brushes ends here. My brushes will no longer appear in your Taobao search results, almost eliminating the possibility of you buying my brushes again. This ensures you won’t encounter a seller like me – after all, one less seller like me means one less opportunity for you to feel frustrated.

Qi Ming’s Personal Reflections

I often struggle with this: many calligraphy enthusiasts who buy brushes from Qi Ming Wen Fang are beginners. Many probably came to my shop after reading my articles. Many of my articles about Chinese brushes or the Four Treasures of the Study are actually very basic content. It’s precisely because people don’t understand these basics that they search online, find my articles, and then come to my shop.

Some friends might buy brushes after reading my entire series of articles (these friends are usually careful and thoroughly investigate their questions until they find answers). Some might come after reading just one article. Some might randomly enter my shop while browsing Taobao, glance at the pictures, and place an order. And some friends don’t even finish reading the detailed introduction and user experience I wrote for each product.

For example, in every brush introduction, I mention the brush head size (tip length and diameter) and what character size the brush is best suited for. Regarding brush preparation, I mention following my official account (Official Account ID: qiminglaoshi) and replying “开笔” (brush preparation). For brush washing and maintenance, you can reply “洗笔” (brush washing), etc. As for shipping, Qi Ming Wen Fang’s official shipping partners are J&T Express and ZTO Express, which usually take 3-5 days, though it might be slower during holidays or big sales…

These questions, which could originally be answered by reading the product descriptions, end up requiring both buyer and seller to spend much more energy communicating. Communication requires time investment. For small operations like mine with only me as customer service – and I’m not always online – this cost might be small. For large shops hiring multiple customer service representatives to answer these questions, this becomes a significant labor cost, and increased costs inevitably lead to higher prices.

Of course, if you’re a beginner and, after reading multiple brush descriptions in my shop, still don’t know how to choose, I warmly welcome you to chat with me through Taobao messenger or WeChat. As I’ve said before, while I might not reply immediately, I will definitely reply when I see your message.

I apologize for any inconvenience this may cause you, and I hope for your understanding.

Finally, I also want to apologize to all the friends who have been following and supporting Qi Ming. Sometimes I don’t reply promptly to messages on WeChat, Taobao, and other platforms, but I will definitely reply when I see them. Thank you for your understanding.