Recently, some calligraphy enthusiasts in the Qi Ming calligraphy group asked about two fundamental brushwork techniques in Chinese calligraphy. Today, Qi Ming will explain these techniques by referencing an article from City Business Daily, along with helpful images to make these concepts easy to understand. This guide will help anyone learning Chinese calligraphy improve their brush stroke skills.

Two Essential Stroke Techniques Explained

Inner containment (nèi yè, 内擫) and outward expansion (wài tuò, 外拓) are two important concepts you’ll frequently encounter when studying Chinese calligraphy. Throughout calligraphy history, these terms have been interpreted in different ways by various masters.

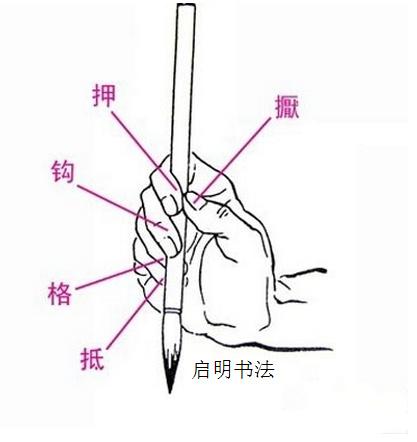

According to the Kangxi Dictionary, the character 擫 means “to press with one finger.” Inner containment means pressing inward with one finger while writing. The character 拓 (tuò) means “to support or push an object with the hand.” Outward expansion means using your fingers to lift upward and push outward.

Diagram of the five-finger brush holding method

For details on the five-finger Chinese brush holding method, please refer to “Standard Chinese Brush Holding Methods and Positions (with Illustrated Guide to Holding a Chinese Brush)”

The Historical Origin of These Techniques

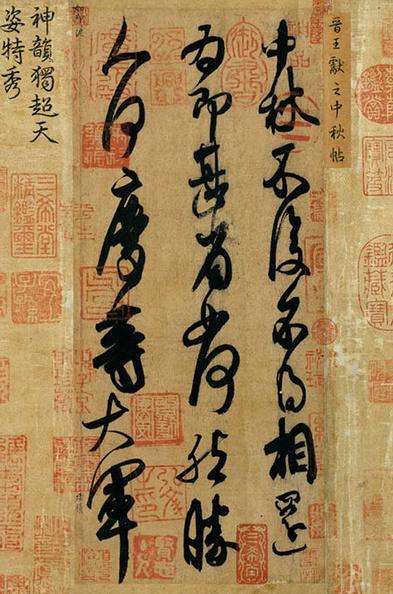

These two terms first appeared in Yuan Dynasty scholar Yuan Pou’s work General Discussion of Calligraphers. In this book, he wrote: “Wang Xizhi used inner containment in his brushwork, gathering the brush tip inward, resulting in imposing strength and strict structure. His son Wang Xianzhi used outward expansion, opening up the brush strokes, resulting in a relaxed and varied style.”

This passage means that Wang Xizhi applied inward pressure with his Chinese brush, keeping the brush tip contained. This technique created characters with commanding presence and rigorous composition.

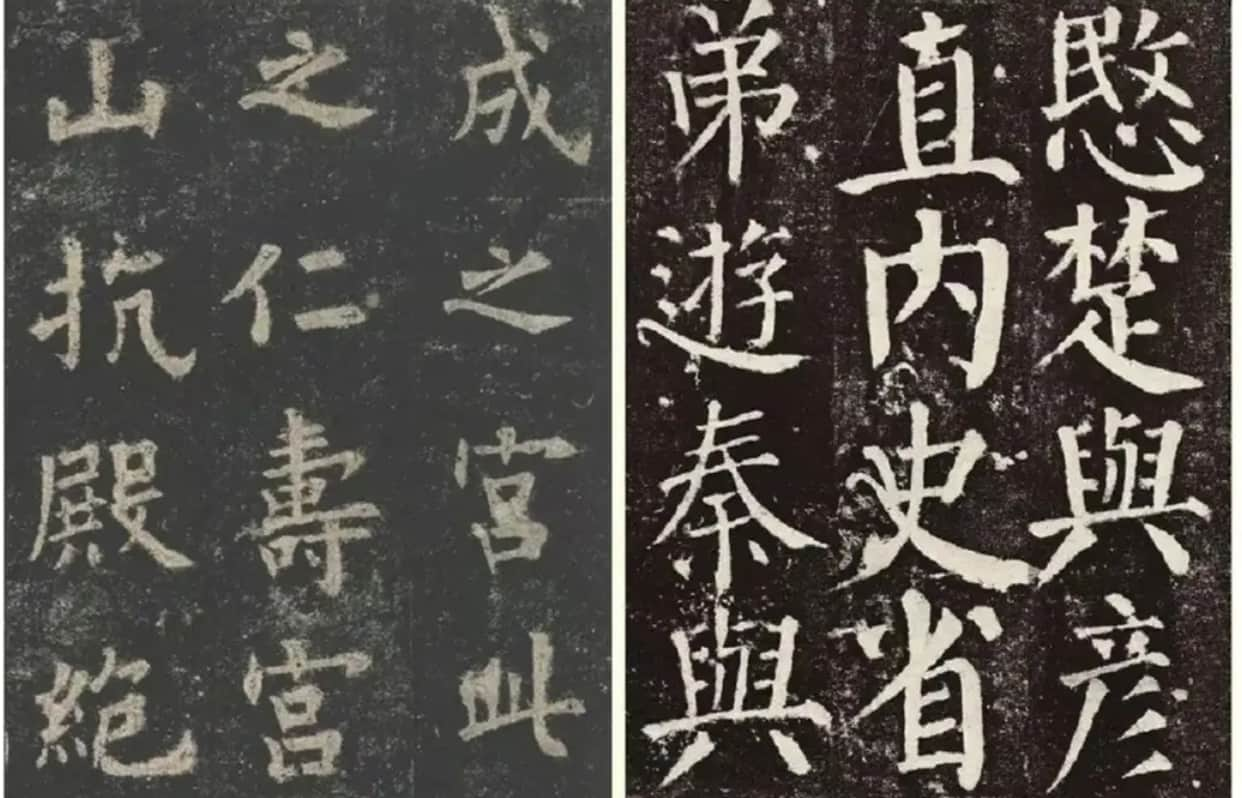

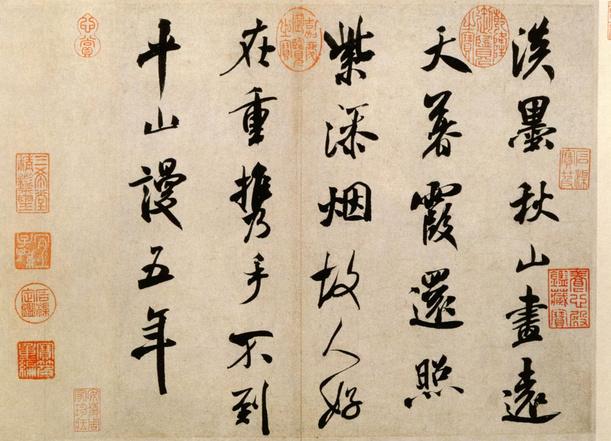

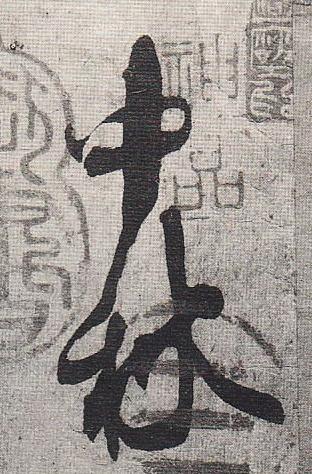

Wang Xizhi’s Timely Clearing After Snowfall

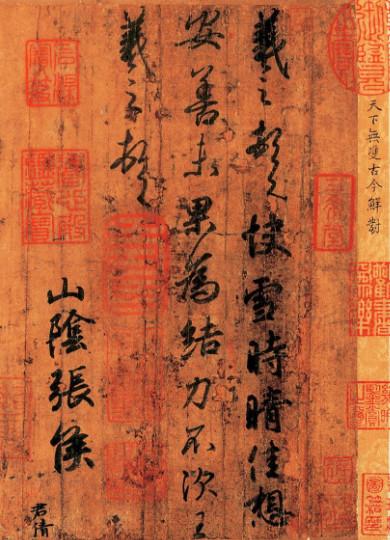

His son Wang Xianzhi extended his brush strokes outward, creating calligraphy works with diverse techniques and countless variations in style.

Because father and son used different brushwork methods with their Chinese brushes, they produced characters with distinctly different shapes and styles.

Wang Xianzhi’s Mid-Autumn Post

Two Legendary Masters: The “Two Wangs”

Wang Xizhi excelled in regular script (kaishu) and running script (xingshu), while Wang Xianzhi stood out in running script and cursive script (caoshu). Both achieved remarkable success in calligraphy, though in different ways, and both reached the pinnacle of the Chinese calligraphy world.

Wang Xizhi is respectfully known as the “Sage of Calligraphy.” Together, Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi are called the “Two Wangs” in the calligraphy world. The title “Wang” carries the weight of “great king.” Both father and son being honored with this title is well-deserved.

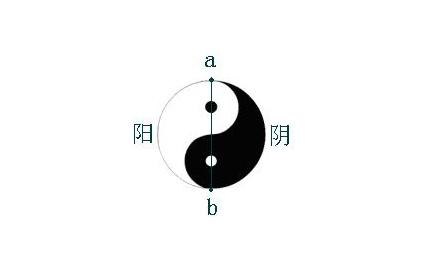

The Bagua diagram from Chinese Taoist culture

The “Two Wangs” are deeply respected and admired by calligraphers and calligraphy enthusiasts throughout history. Their calligraphy has been eagerly studied and imitated by generations of practitioners. Great calligraphers like Ouyang Xun, Yan Zhenqing, Liu Gongquan, Yu Shinan, and Sun Guoting all took pride in having studied the “Two Wangs'” calligraphy techniques.

(Qi Ming’s note: For more on this topic, you can refer to the article “Was Wang Xizhi’s Brushwork Passed Down? What Should We Learn When Studying Calligraphy?” This article clearly outlines the transmission lineage of Wang Xizhi’s brush techniques.)

How to write with inner containment like Wang Xizhi and with outward expansion like Wang Xianzhi became a hot topic among calligraphers throughout history. It remains a goal pursued by Chinese calligraphy enthusiasts today.

Three Ways to Understand These Techniques

How can we understand the “Two Wangs'” writing methods through inner containment and outward expansion? From the Yuan Dynasty to today, calligraphers and enthusiasts from different periods have explored this question from various angles, offering different interpretations based on their own practice.

These interpretations can be summarized into three categories:

First, exploring brushwork methods through the literal meanings of inner containment and outward expansion.

Second, exploring the line characteristics of the “Two Wangs'” characters through the lifting and lowering movements in these techniques.

Third, exploring the structural features of the “Two Wangs'” characters through the direction of the “arch” between two parallel vertical lines.

In summary, everyone is trying to decipher Yuan Pou’s statement and unlock the secrets of these master techniques.

How to Practice: The Hand Movement Method

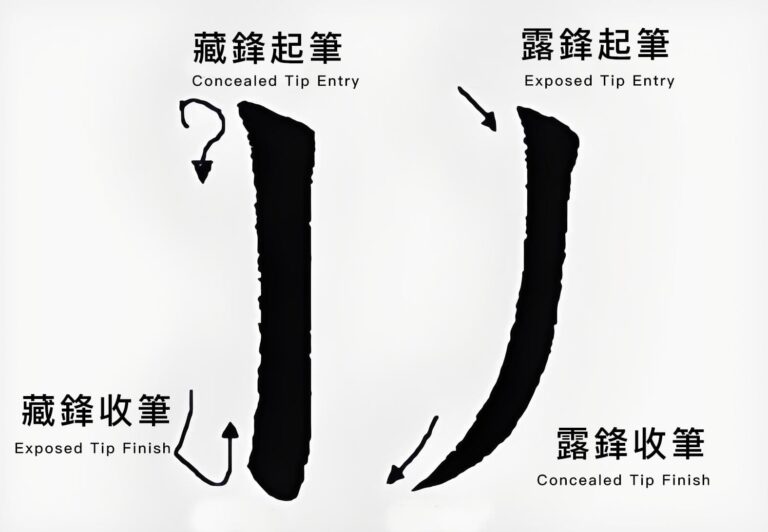

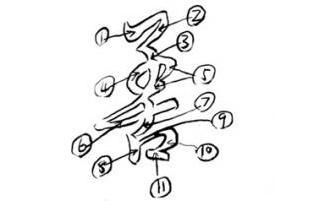

Diagram showing the stroke direction of inner containment and outward expansion

This interpretation is represented by calligrapher Ms. Sun Xiaoyun. In her book There Are Methods in Calligraphy, she explains the hand movements: “When turning the Chinese brush to the right, with the palm facing inward, the index, middle, and ring fingers each apply force – this is ‘inner containment.’ ‘Outward expansion’ works in the opposite way: the thumb presses the brush shaft, referring to leftward brush movement.” She continues: “Inner containment and outward expansion describe the continuous state of hand movements.”

This technique involves rotating the Chinese brush shaft using twisted brush movement. It explains that pressing or pushing down creates one type of stroke, while lifting or pushing creates another – two types of actions moving in different directions.

This method uses you, the calligrapher, as the reference point. When your palm faces toward you, that’s inward. During inner containment, your index, middle, and ring fingers press down on the brush shaft, pulling or turning it inward and to the right.

At the same time, your thumb lifts the brush shaft and pushes it to the left, thus completing outward expansion simultaneously. Using this method involves two actions, two directions, and one continuous process. It’s completed in a single motion.

In other words, inner containment and outward expansion cannot be completed separately when using a Chinese brush.

Understanding the Primary and Secondary Techniques

With this method, when we say a stroke uses inner containment, we mean it’s primarily inner containment with secondary outward expansion. Similarly, when we say a stroke uses outward expansion, it means primarily outward expansion with secondary inner containment.

The two techniques complement each other and cannot exist independently. For simplicity in practical application, we simply say “inner containment” or “outward expansion.”

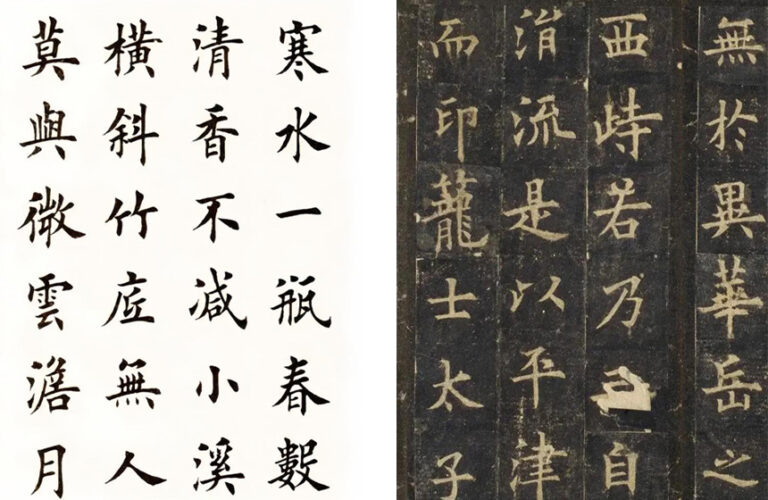

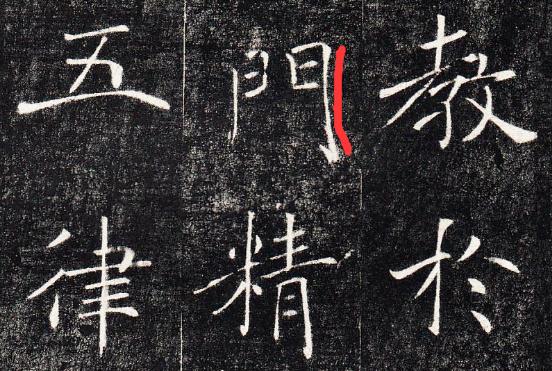

Chu Suiliang’s Preface to the Sacred Teachings at the Wild Goose Pagoda, with annotations showing typical inner containment brushwork

It’s important to emphasize that since you, the calligrapher, serve as the reference point, pressing the Chinese brush toward yourself is inward, and pushing outward is outward. Therefore, pressing and turning the brush to the left with your index, middle, and ring fingers is also inner containment. Similarly, extending and turning to the right with your thumb is also outward expansion.

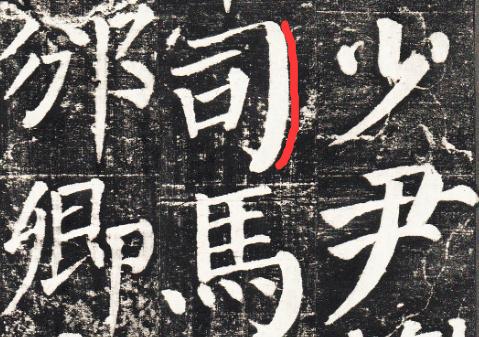

Yan Zhenqing’s Qinli Stele, with annotations showing typical outward expansion brushwork

If you understand it this way, then when you actually practice these two Chinese brush techniques – inner containment and outward expansion – you’ll be able to handle any situation smoothly and skillfully. You won’t be limited to only turning right for inner containment and only turning left for outward expansion, which would leave you confused and flustered.

Practical Examples: Analyzing Real Characters

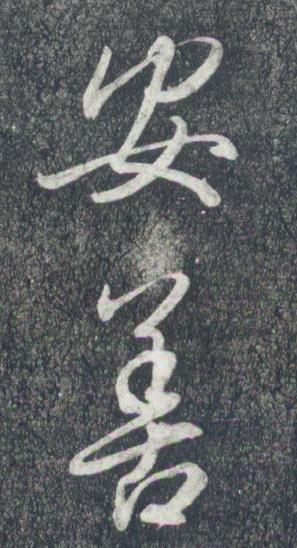

To illustrate this point, let’s analyze two characters “an” (安) and “shan” (善) from Wang Xizhi’s Timely Clearing After Snowfall using these brushwork methods:

Detail from Wang Xizhi’s Timely Clearing After Snowfall

(For convenience of explanation, we’ll use abbreviations: “inner” represents “primarily inner containment” and “outer” represents “primarily outward expansion.”)

First character, “an” (安): The stroke sequence follows: inner-outer-inner-inner-inner-inner-outer-inner

Second character, “shan” (善): The stroke sequence follows: outer-inner-inner-outer-inner-outer-inner-inner-outer-inner-outer

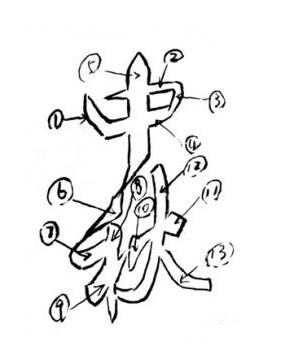

Using the same method, let’s analyze two characters “zhong” (中) and “qiu” (秋) from Wang Xianzhi’s Mid-Autumn Post:

The character breakdown: outer-outer-inner-outer-inner-inner-outer-inner-outer-outer-inner-inner-outer

Key Takeaways for Learning Chinese Calligraphy

From exploring with this method, we can see an important principle: Wang Xizhi’s brushwork emphasizes inner containment as the primary technique, while Wang Xianzhi’s brushwork emphasizes outward expansion as the primary technique.

However, using only inner containment or only outward expansion won’t work when practicing Chinese brush calligraphy. Both techniques must work together, with one being primary and the other supporting, to create beautiful and authentic Chinese calligraphy strokes.

By understanding and practicing these two fundamental techniques, you’ll be able to better appreciate and replicate the masterful brushwork of China’s greatest calligraphers.

You May Also Like:

Top 10 Chinese Calligraphy Brushes: The Ultimate Guide to Selection and Care

Why Slender Gold Style Isn’t the Best Choice for Beginners in Chinese Calligraphy

Mastering Center-Tip Brushwork in Chinese Calligraphy

What Are Resting Wrist, Suspended Wrist, Suspended Elbow and How to Choose?

How to Prepare and Care for Your Chinese Calligraphy Brush: A Beginner’s Guide