When it comes to Chinese brush handles, I’ve learned quite a few lessons through trial and error. When I first started customizing the Qingquan Chinese brush, I used green bamboo handles. However, some calligraphy enthusiasts reported that the green bamboo handles tended to crack easily.

Later, I asked my followers to vote on alternatives, and we ultimately chose imitation bamboo steel handles (hollow) for the new Qingquan Chinese brush. After that, we also tried wooden handles and imitation wood hollow steel handles.

Now, we’ve decided to use reinforced bamboo handles to prevent cracking, so our online store currently sells mainly the bamboo handle version of Qingquan. But let me get to the main point. Today’s content is actually from Huang Jian’s basic calligraphy tutorial. Since we’re discussing Chinese brush handles, I wanted to share some background first. Below are my notes from Huang Jian’s basic calligraphy tutorial.

Full text follows:

Let’s talk about brush handles. This is actually quite a complex topic, so I can only cover the basics here.

1. Materials for Chinese Brush Handles

First, let’s discuss the materials used for brush handles. In ancient times, brush handles were made from both bamboo and wood. During the Warring States period and the Qin and Han dynasties, some brushes used wooden handles, probably because wood was more abundant in northern regions while bamboo was scarce.

Historical records mention that Meng Tian, the inventor of the Chinese brush, also used wooden handles. Bamboo handles are called “brush tubes.” After the Wei and Jin dynasties, bamboo tubes became the standard material.

The passage in the image above discusses the question of elegance versus commonness – in other words, taste. Bamboo symbolizes the virtue of a gentleman and offers excellent value for money. Ancient scholars typically used bamboo handles for their Chinese brushes.

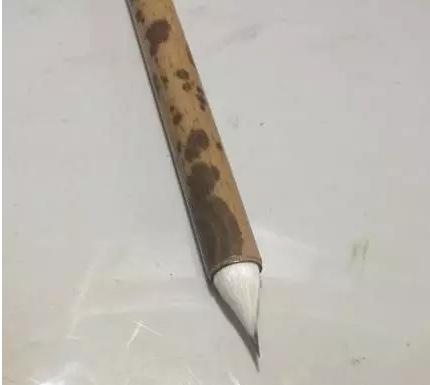

Spotted bamboo, also known as Xiangfei bamboo, has dark spots on its stalks. (Qi Ming’s note: My hometown, Junshan Island in Yueyang, Hunan, has abundant Xiangfei bamboo growing naturally, which is something that makes me especially proud of my hometown.

Of course, nowadays there are also many artificial Xiangfei bamboo handles on the market. These are mass-produced using computer-generated patterns that imitate Xiangfei bamboo spots. Generally speaking, these artificial handles have very similar patterns and lack the natural quality of genuine Xiangfei bamboo – they look more rigid. After all, each genuine Xiangfei bamboo handle is different and unique.)

The Shosoin repository in Japan houses several Chinese brushes from the Tang dynasty, as well as ancient Japanese-made brushes, and most of them use spotted bamboo.

This is a replica of a Tang dynasty chicken-spur brush from Japan’s Shosoin that I use myself.

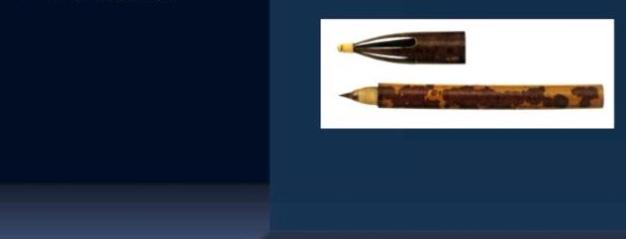

On the market today, you commonly find green handles and red handles. Red handles are dyed. (Qi Ming’s note: There are also black handles, like the Chinese brush I bought online shown in the image below.

Black brush handles are actually also treated with dye.

The Book of Songs, in the “Quiet Maiden” section, mentions “The quiet maiden so lovely, gave me a red tube.” This red tube refers to a red-colored handle. In ancient times, female historians in the imperial palace, as well as Han dynasty officials in the Imperial Secretariat, all used red handles.

(Qi Ming’s note: Regarding the “red tube” mentioned here, there’s no definitive explanation. Some say it’s a red-handled brush, while others say it might be the same as “ti” (white cogongrass, which symbolizes marriage). Some plants are red when they first sprout or shortly after germination – not only are they brightly colored, but some are even edible. However, it might also refer to a tube-shaped musical instrument painted red.)

2. The Thickness of Brush Handles

Now let’s talk about the thickness of brush handles. Why were brushes from the Warring States, Qin, and Han periods so small and thin? There are two reasons:

First, brush heads at that time were small with few layers – sometimes they had no distinct layers at all. Second, people had the habit of inserting brushes into their hair, so the handles were very thin.

Ancient people had hair buns where they could insert brushes. Later, as brush heads became larger, the handles also became thicker, and this habit gradually disappeared.

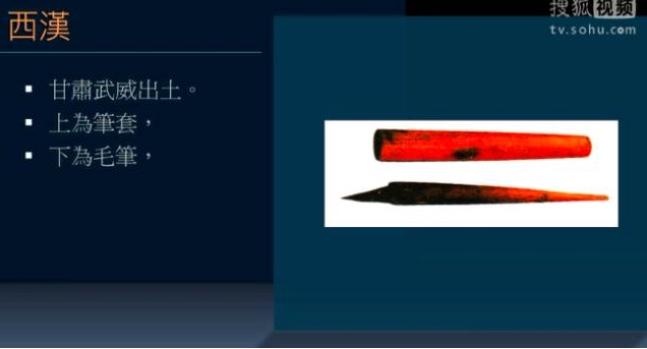

This is an excavated Western Han dynasty Chinese brush. The brush head has already been enlarged, and the handle is relatively thick. However, one end is still sharpened to make it easier to insert into a hair bun.

After Zhang Zhi and Wei Dan at the end of the Han dynasty, true calligraphy brushes emerged, and people gradually began using hollow bamboo tubes.

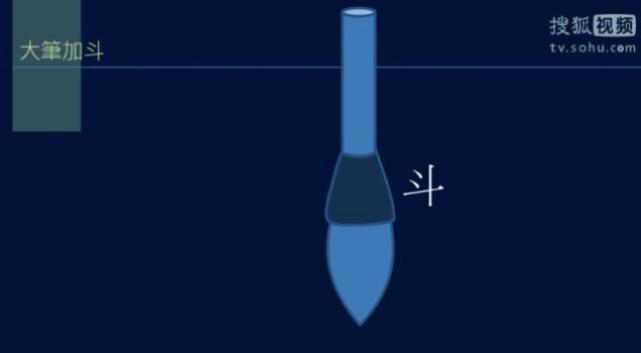

Bamboo tubes present a problem: if they’re too thick, they’re hard to grip. If the brush head is very large, you need to add a collar rather than using one large bamboo tube.

At this point, let me explain why the Qingren Chinese brush I customized doesn’t use only a bamboo handle like the Qingquan brush does. This is because the Qingquan brush (old jade bamboo version) has a maximum bristle diameter it can support. If it were any larger, we would need bigger bamboo, which would inevitably make the handle too thick to grip comfortably.

This is the first Qingquan bamboo handle Chinese brush I customized – no collar.

Look at the middle brush – the handle is very thick, and the hollow interior is even larger than the brush head diameter. So they installed a smaller black tube at the front to house the brush head. The real collar brush is the bottom one – the handle itself isn’t thick, but because it has a collar, it can accommodate a very large brush head.

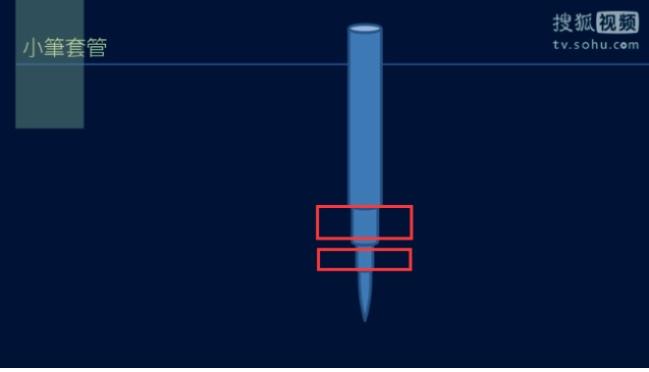

If the brush head is very small, instead of making the entire handle extremely thin bamboo, you use a sleeve tube. Sometimes you can layer several sleeve tubes. The advantage of adding sleeve tubes is that the part of the handle you grip doesn’t need to be made very thin.

This is an example of a brush using sleeve tubes – the brush head can be very small.

Qi Ming Wen Fang’s Qinghui brush uses this sleeve tube technique. This is a pure wolf hair Chinese brush from Qi Ming Wen Fang called Qinghui, which uses this technique. – Qi Ming’s note

3. The Length of Brush Handles

How long should a brush handle be? Wang Chong of the Han dynasty, the author of “Balanced Discussions,” said: “A knowledgeable and capable person needs a three-inch tongue and a one-foot brush.” This means intelligent and capable people need to know how to speak well and write well.

A foot in the Han dynasty was approximately 23 centimeters. From excavated Han dynasty brush handles, we can see the length was indeed standardized at around 23 centimeters. By the Tang dynasty, brushes had become thicker and were no longer inserted in hair, so they also became shorter.

A photo sent to me by one of Qi Ming’s followers.

An old version of Qi Ming Wen Fang’s Qingquan Chinese brush.

Qi Ming’s note: When I first released my customized Chinese brush, some calligraphy enthusiasts said the handle was too long (first image above) and didn’t feel right in hand. So one person cut off a section himself and sent me a photo. I also tried cutting mine shorter and found that it indeed improved the feel. So when I placed the next order, I asked the craftsman to use shorter handles (second image above).

The Tang dynasty calligrapher Yu Shinan wrote in “Essay on Brush Essence”: “A brush should be no longer than six inches.”

From the dozen or so Tang dynasty brushes in Japan’s Shosoin collection, the length is approximately 17 to 19 centimeters, which equals about 5.5 to 6 Chinese market inches today.

Currently on the market, green handles are about 18 centimeters and red handles are about 21 centimeters – similar to Tang brushes, just about two centimeters shorter than Han brushes. The longer the handle, the more easily it bends. Look at the one below – it’s too long and clearly bent.

How to check if a Chinese brush handle is straight.

The brush handle must be straight. When you buy a Chinese brush, the inspection method is very simple: place it on a table or glass surface and roll it. You can immediately feel whether it’s straight. If you hear clicking sounds when you roll it – tap tap tap tap – then it’s not straight.

(Qi Ming’s note: Regarding this point, I believe the main thing is that the brush should be round. Even if the handle is slightly bent, it’s not a big problem and won’t significantly affect your calligraphy.)

Note: This article is based on my notes from Episode 9 of “Huang Jian’s Basic Calligraphy Tutorial” titled “Understanding the Chinese Brush 2.” I will continue organizing other notes, so please stay tuned. You might also be interested in the following articles.

How to Break in a New Chinese Calligraphy Brush

Top 10 Chinese Calligraphy Brushes: The Ultimate Guide to Selection and Care

How to Clean Chinese Calligraphy Brushes: Water-Saving Method That Keeps Your Sink Clean

Are Nylon Calligraphy Brushes Really Bad Quality?

Chinese Calligraphy Brush Splitting: Prevention Tips and Easy Fixes

How to Choose the Right Chinese Calligraphy Brush Size for Your Writing