In our previous article, we explored Japan’s main brush-making regions and manufacturing processes. Now, let’s dive into a topic many calligraphers and artists are curious about: What is the difference between Chinese and Japanese brushes? While both are essential tools for East Asian calligraphy, their unique characteristics in hair, shape, and handle design can significantly influence a piece of art. Understanding these key distinctions is crucial for choosing the right brush for your creative needs.

Compared to China’s vast territory and abundant resources, Japan faces significant challenges in sourcing raw materials for brush making. This includes high-quality animal hair suitable for brush tips, beautiful bamboo poles with natural patterns, and various precious materials for brush handles.

This resource limitation may explain why, over the past 2,000 years, Japan has repeatedly invaded China due to territorial and resource concerns, while Chinese dynasties following Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist principles never invaded Japan.

Material Sourcing and Manufacturing

Due to these raw material limitations, many brushes sold in Japanese calligraphy stores actually come from Chinese brush-making regions, particularly from the Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces.

According to what Qi Ming has learned, many brush workshops in Yangzhou rarely sell their products domestically. Instead, most of their output goes to Japan. Qi Ming Wen Fang also works with these multi-generational family workshops for brush production.

According to factory owners, Japanese buyers have extremely high quality standards. In earlier years, they would even weigh brush tips on scales and use fixed wire rings to measure diameters during inspection.

These domestic brush workshops manufacture for major Japanese brands including Gyokusendo, Kyukyodo, Kiya, Kobaien, and Bokuundo.

Key Manufacturing Differences

Japanese and Chinese brushes differ in both processing techniques and material selection. Generally speaking, Japanese brush tip processing doesn’t include the water basin procedure, uses different degreasing processes, and employs welding techniques that differ from Chinese brush-making methods.

In terms of materials, besides traditional sheep hair, wolf hair, purple hair, and pig bristles, Japanese brush makers commonly use cat hair, deer hair, and various bird feathers.

What is the difference between Chinese and Japanese brush?

1. The difference between Chinese and Japanese brush-Hair Materials and Formulations

One distinctive feature of Japanese brushes is their unique hair blend ratios. Unlike Chinese traditional brushes that often use single or few hair types, Japanese brushes tend to combine multiple hair types with different characteristics.

This is especially true when creating the brush core and outer layers, where they blend various materials to achieve more complex brush performance. This might be due to material scarcity, or they may have preserved better ancient Chinese brush-making traditions – it’s hard to say for certain.

2. The difference between Chinese and Japanese brush-Brush Tip Shape and Fullness

Regarding brush tip shape, there are indeed differences between Chinese and Japanese brushes. Simply categorizing by “tip length” isn’t accurate, as tip length isn’t the core difference.

The key distinction is that Japanese brush tips typically contain richer hair materials, giving the brush head a fuller feeling during writing, similar to Huzhou-style brushes. This design allows the brush tip to hold more ink.

3. The difference between Chinese and Japanese brush-Manufacturing Process: “Dry Method” and Softer Performance

Japanese brushes use a unique “dry method” manufacturing process, meaning they don’t use the “water basin” technique. This method produces relatively softer brushes that better meet the demands of Japanese calligraphy.

Japanese calligraphy includes Chinese character calligraphy, kana script, and modern poetry combining both scripts – Qi Ming’s note. These styles require delicate stroke variations and layered ink tones.

In the complex Hu brush manufacturing process, the water basin procedure is the most refined and crucial step. Brush makers sit by wooden basins, holding horn combs, carefully combing degreased hair materials. They select each hair individually, classifying and combining them based on color, tip quality, and softness to create blade-shaped hair bundles.

Next, they place the materials in water, meticulously removing broken, blunt, curved, or flat hairs. This entire process requires exceptional patience and skill.

4. The difference between Chinese and Japanese brush-Hair Combing Tools and Efficiency

During hair combing, Japanese brush makers use small combs. While this method may not be as refined as traditional Chinese craftsmanship, it is more efficient. This small but significant detail is just one example of the difference between Chinese and Japanese brushes, as makers from both countries employ unique methods to achieve their desired results. Despite the seemingly simple combing method, you have to admire the solid craftsmanship of Japanese brush makers, who still manage to create extremely neat brush tips.

Other Observations and Discoveries

Common Ground: Both Japanese and Chinese brushes now commonly use “water brush” manufacturing techniques (according to Qi Ming’s understanding, the term “water brush” is more popular in the Yangzhou area) and apply “inner lining” technology inside brush tips to enhance elasticity and performance. This modern technique has replaced the ancient method of wrapping brush heads in circles.

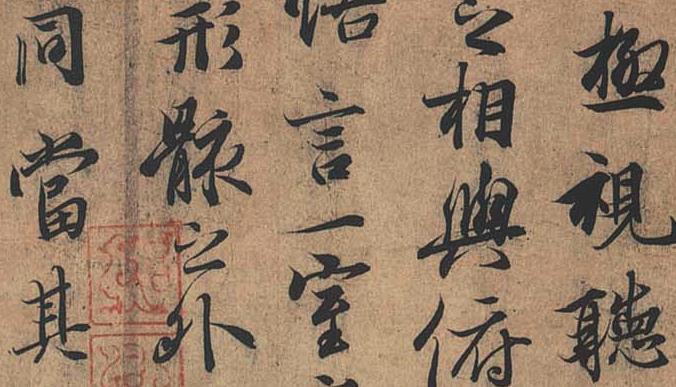

Recommended Reading: Tang Dynasty Legacy: Tang Dynasty Brushes in Japan’s Shosoin Repository

Complexity and Refinement: Although Japanese brush-making processes appear more complex from the outside, overall, their craftsmanship’s refinement may not match Chinese brushes – at least in the “water basin” step, which Japanese brush makers skip entirely.

Of course, they might work more carefully, still ensuring excellent brush quality without the water basin process. If that’s truly the case, we must admire these masters’ superior skills.

Family Heritage in Japanese Brush Making: In some Japanese brush shops, brush makers work in family units. This is also the main organizational structure for most Chinese brush manufacturers.

However, Japan’s brush-making industry indeed lacks factory-scale production, while China has it. Qi Ming has previously visited Wengang in Jiangxi and Yangzhou in Jiangsu, seeing brush factories with thousands of square meters of workshop space and dozens of workers on assembly lines.

You could say this reflects Japan’s commitment to traditional handcrafts, or you could say their supply chain scale cannot support factory production. Under this model, one brush might be completed by multiple family members working together, though brushes from Nara are reportedly completed entirely by one person.

Production scene at a large brush manufacturing factory in Yangzhou (photographed by Qi Ming)

Material Sources: Notably, most hair materials for Japanese brushes depend on imports. Sheep hair, raccoon hair, and wolf hair mainly come from China. There’s also material from Russia.

Rabbit hair brushes aren’t common in Japan. When they exist, they’re usually finished products imported from China, or Japanese brush makers import Chinese rabbit hair and craft the brushes themselves.

Shopping Tips for Japanese Brushes

If you’re planning to buy brushes in Japan, try to purchase directly from brush makers’ homes when possible. If shopping at regular calligraphy supply stores, ask clearly whether the brush is made in Japan or imported from China.

There’s no need to travel all the way to Japan only to buy Chinese-made products, especially since prices increase significantly after crossing the ocean, offering poor value. Domestic purchases benefit from price competition among various manufacturers.

History of Brush Introduction to Japan

I’d also like to share some historical knowledge about how brushes entered Japan. This information comes from collecting and organizing existing online materials.

Early Stage (Late 4th Century)

With the introduction of Chinese character culture, brushes as writing tools also entered Japan. However, Japan hadn’t yet developed systematic writing habits, so brushes were mainly used for records and official documents.

Development Stage (Asuka to Nara Periods, Mid-6th to Late 8th Century)

As Buddhism spread from China to Japan (many Chinese monks like Jianzhen traveled to Japan to spread Buddhism, while Japanese monks like Kukai came to China to study), brushes, ink, and papermaking techniques also spread.

The popular activity of copying Buddhist scriptures promoted brush adoption and development in Japan.

Maturation Stage (Heian Period, 794-1185)

Japanese calligraphy gradually matured and formed unique styles. Japanese monks and envoys returning from Tang China, such as Kukai, brought back a wealth of knowledge on brush-making techniques and calligraphy masterpieces. This cultural exchange laid the foundation for the difference between Chinese and Japanese brushes that we see today, as the Japanese brush industry developed unique characteristics based on these influences.

During this period, Japan created unique “kana” characters based on Chinese characters, making brush writing more diverse.

Overall, after entering Japan, brushes evolved from simple recording tools to artistic expression forms, ultimately deeply integrating with local Japanese culture to form unique Japanese calligraphy art.

Conclusion

If this article helped you understand the difference between Chinese and Japanese brushes, please share it with other calligraphy enthusiasts who might find it useful.

Finally, I’d like to share a quote I personally love, and I hope overly radical nationalists won’t leave inappropriate comments:

“Civilizations become richer and more colorful through exchanges and mutual learning. Such exchanges and mutual learning serve as an important driving force for human progress and world peace and development.”

— Xi Jinping’s speech at UNESCO Headquarters, March 27, 2014