Today’s article is actually notes that Qi Ming took while listening to Huang Jian’s beginner calligraphy course. In this lesson, Teacher Huang Jian mainly introduced us to some ancient Chinese brush making methods and their evolution.We believe that after reading this, you will have a better understanding of ancient Chinese brush construction and the materials used in brush making.

The full article is as follows:

Today we’ll talk about the Chinese brush. Chinese characters are written with Chinese brushes. The brush, ink, paper, and inkstone are called the “Four Treasures of the Study,” and the most important among them is the Chinese brush.

How Ancient Chinese Brushes Were Made and Materials?

In the Qing Dynasty, Yang Bin wrote in “Da Piao Ou Bi《大瓢偶笔》”: “Whether calligraphy is good or not depends half on the brush.” To write good calligraphy, technique is certainly important, but whether the Chinese brush is good or not is also a crucial factor. Today I’ll explain what kind of Chinese brush is used for calligraphy.

How ancient Chinese brush heads were made?

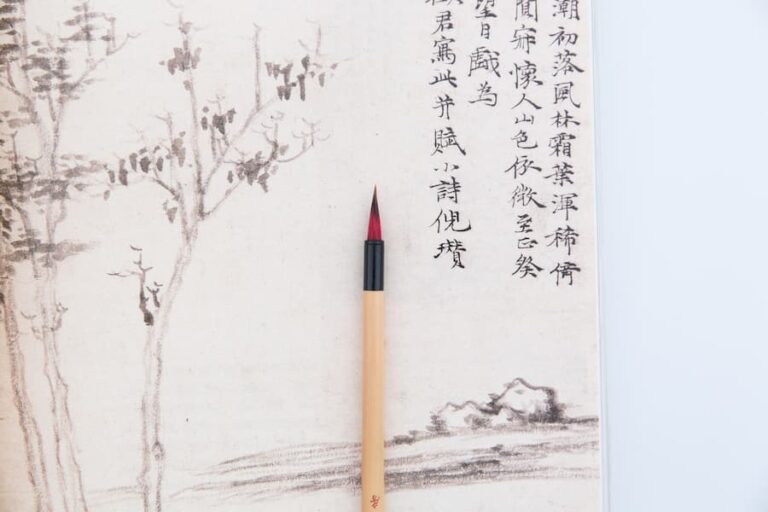

China has been using Chinese brushes for thousands of years. Traces of Chinese brushes can be found on ancient pottery. What were ancient Chinese brushes like? A Chinese brush consists of a handle and a brush head, with the key being the construction of the brush head. From the actual Chinese brushes unearthed today, we can see four main types of brush head construction.

Bundle the brush hair and tie it to one end of a small wooden or bamboo stick, and it becomes a Chinese brush.

The Simplest and Most Primitive Method

The earliest Chinese brushes looked like brooms. The brush hair was bundled and tied to one end of a small wooden or bamboo stick to form a Chinese brush.

The center of this type of Chinese brush is hollow.

If we examine this closely, we can see that the center of this type of Chinese brush is hollow. When pressed down while writing, the brush hairs easily spread apart.

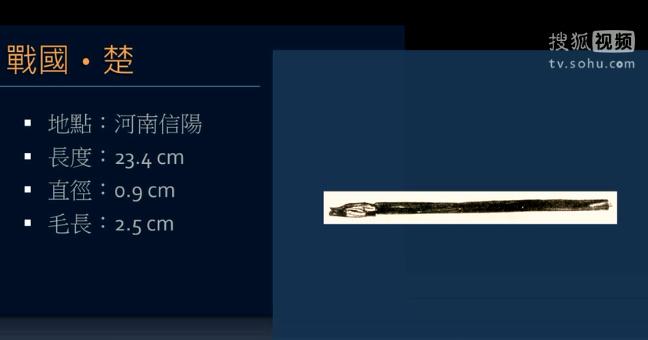

Ancient Chinese brush from the Warring States period unearthed in Xinyang, Henan Province

A Chinese brush unearthed in 1957 from a Warring States tomb at Changtaiguan in Xinyang, Henan Province, was this type of externally-tied Chinese brush. The handle was a small bamboo stick, 23.4 centimeters long in total. The handle diameter was 0.9 centimeters, the brush tip was 2.5 centimeters long, and the brush hair was tied to the handle with rope.

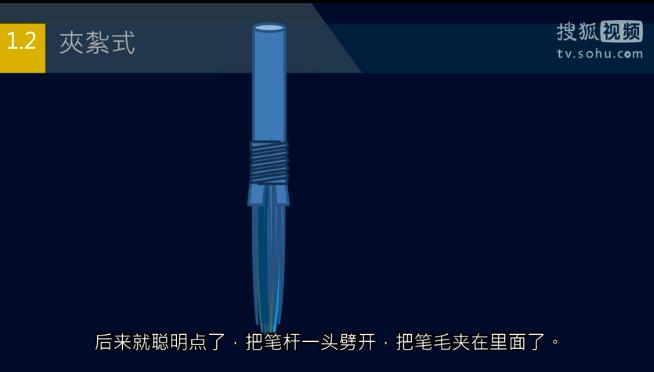

Later, people became smarter. They split one end of the handle and clamped the brush hair inside.

An Improved Design

Later, people became smarter. They split one end of the handle and clamped the brush hair inside. This improvement brought the brush hairs closer together, meaning the brush head center was no longer hollow.

Ancient Chinese brush unearthed in Changsha, Hunan Province

In June 1954, a Chinese brush was unearthed from a Warring States Chu tomb at Zuojiagongshan in Changsha, Hunan Province, using this clamping method. The handle was made of bamboo, and the brush hair used premium rabbit hair – specifically rabbit guard hairs. One end of the handle was split into several parts, the brush hair was clamped in the middle, then bound with fine thread, and coated with a layer of lacquer on the outside.

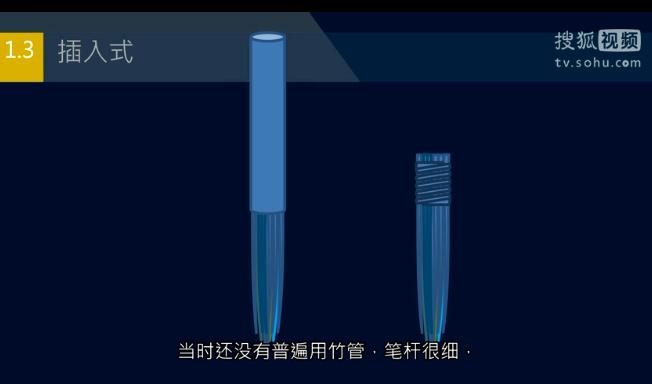

At that time, bamboo tubes weren’t widely used yet, and the handles were quite thin.

The Cavity Method

At that time, bamboo tubes weren’t widely used yet. Handles were generally quite thin, so a hole had to be drilled at one end of the handle to accommodate the brush head. This hole is called the “hair cavity” (Qi Ming note: also called the brush chamber).

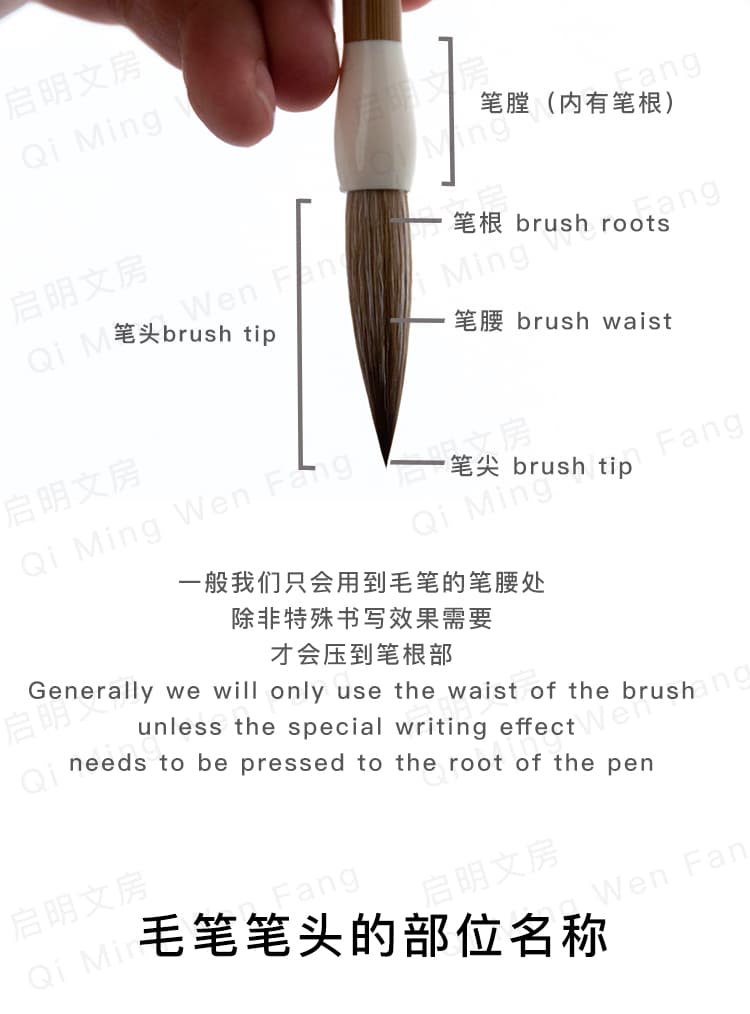

Parts and names of the Chinese brush head

Using Qi Ming’s custom Qingyi Chinese brush to explain brush construction in detail.

Note that at this point, the brush head was made first. The root of the brush head was tightly bound, then inserted into the hair cavity. Making the brush head first was a major advancement in brush-making craftsmanship.

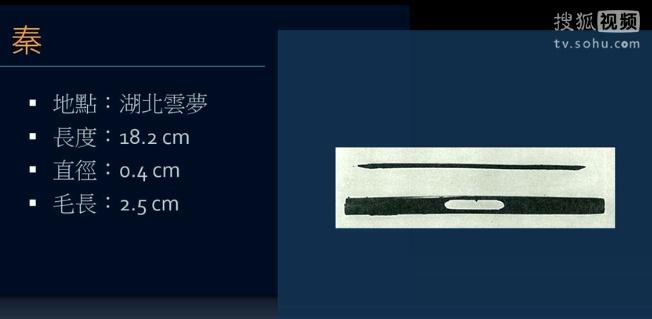

Qin Dynasty Chinese brush unearthed in Yunmeng, Hubei Province

In December 1975, three Chinese brushes were unearthed from a tomb dating to the 30th year of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s reign at Shuihudi in Yunmeng, Hubei Province. The handles were bamboo, thick at the bottom and thin at the top, with one end hollowed out into a cavity where the brush head was inserted. The sixth brush was 18.2 centimeters long, showing that the technique of inserting into brush tubes was already adopted during the Qin Dynasty.

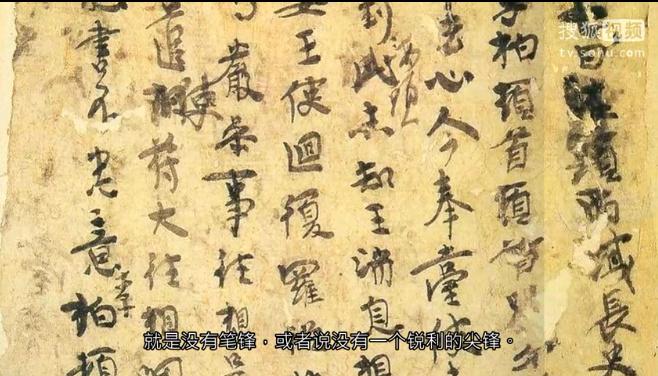

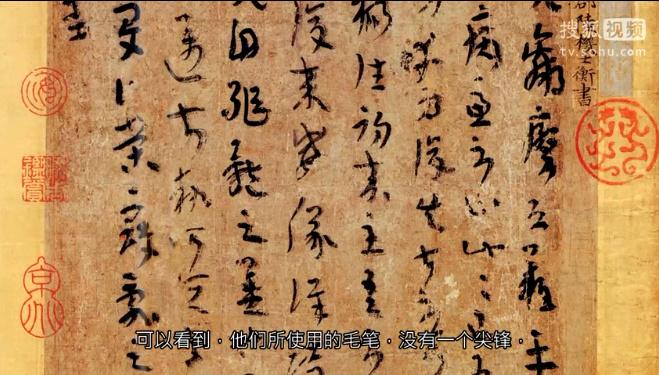

We can see that the Chinese brushes they used didn’t have a sharp tip.

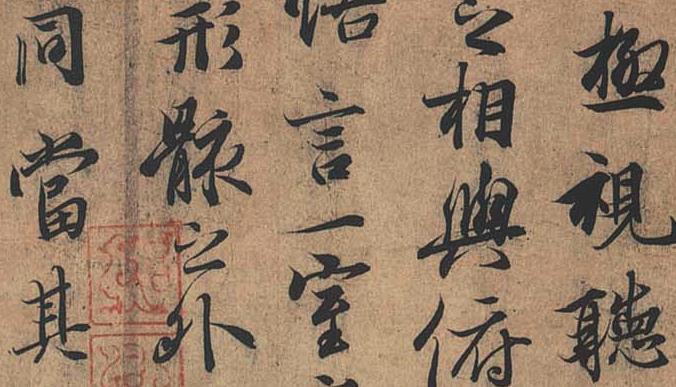

However, this type of brush still had some problems when used. It lacked a brush tip, or rather, lacked a sharp point. Looking at the “Li Bai Document” or Lu Ji’s (Western Jin) “Ping Fu Tie,” we can see that the Chinese brushes they used didn’t have a sharp tip. This wasn’t ideal for calligraphy use.

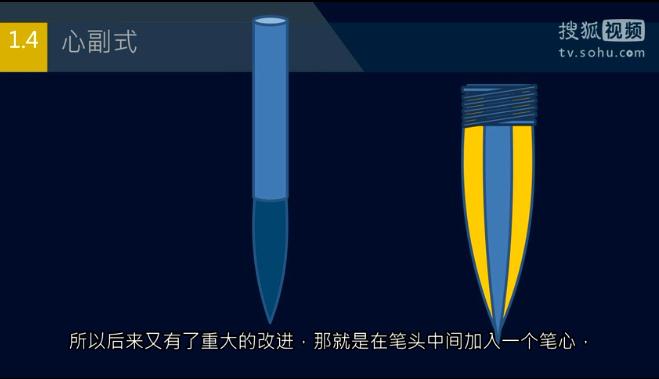

So later there was a major improvement – adding a brush core in the center of the brush head.

The Core System Revolution

So later, there was a major improvement: adding a brush core in the center of the brush head. The brush core was made of stiff hair, elastic and sharp, ensuring a pointed tip. More hair was added around the brush core, which we call secondary hair. This type of brush is called a “core-secondary” style brush.

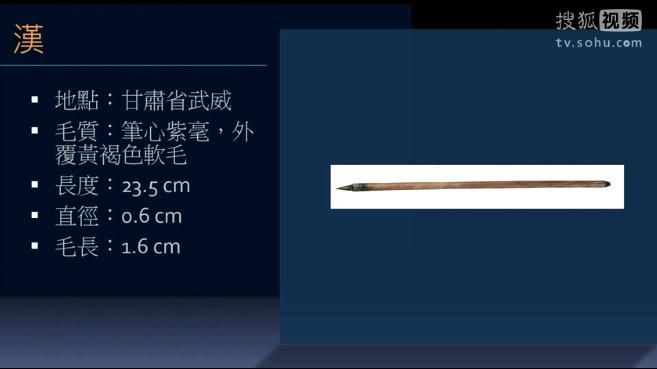

Han Dynasty Chinese brush unearthed in Wuwei, Gansu Province

In 1972, a brush was unearthed from a Han tomb at Mozuizi in Wuwei, Gansu Province. This brush core was made of purple-black stiff hair, covered on the outside with yellow-brown soft hair for better ink storage. The brush tube was bamboo, and after the brush head was inserted, it was bound with silk thread, then lacquered for reinforcement. The handle even had an inscription with three characters: “Baima Zuo,” probably the name of a civilian brush maker. This Chinese brush was very finely made, a big step forward from Warring States brushes.

Now you can probably guess what kind of Chinese brush should be used for learning calligraphy – it must be a Chinese brush with a brush core.

Wei Dan calligraphy brush

The True Calligraphy Brush: “Core Three-Secondary Two-Hair Brush”

A true calligraphy brush is called a “Core Three-Secondary Two-Hair Brush.” This developed around the late Han and Wei-Jin periods, with Wei Dan as the representative figure. Here we have four technical terms: Wei Dan, core system, three secondary layers, and two hair types. Let me explain these.

Wei Dan

Wei Dan, courtesy name Zhongjiang, was from Jingzhao (present-day Xi’an). He was a great calligrapher of the Cao Wei period and also a writer. Moreover, he could make his own brushes and ink – he was a master in this field. His article “Brush Methods” is the most important technical document on brush making. Everyone knows Lu Ban as the patron saint of carpenters; the patron saint of the brush-making industry is Wei Dan.

A craftsman who wishes to do good work must first sharpen his tools

“A craftsman who wishes to do good work must first sharpen his tools” – everyone knows this saying, which was said by Wei Dan. During the Cao Wei period, many palace buildings were constructed, and the emperor ordered Wei Dan to write inscriptions and plaques. Even the brushes and ink provided by the emperor, Wei Dan said were not good. He said: “A craftsman who wishes to do good work must first sharpen his tools. If you use Zhang Zhi’s brushes, Zuo Bo’s paper, and my ink – combining these three items with my hand – then I can display powerful momentum and write a thousand characters in a square inch.”

Wei Dan was saying: if you want me to write inscriptions, I need these three things – Zhang Zhi’s brushes, Zuo Bo’s paper, and the ink I make. With these three things plus my hand, then I can write well. From this passage, we can see that although Wei Dan could make brushes himself, he greatly admired Zhang Zhi’s brushes. This shows that Zhang Zhi’s Chinese brushes were very famous at that time.

“Core system” means that calligraphy brushes must have a brush core.

“Core system” means that calligraphy brushes must have a brush core. To write good characters, the key is knowing how to use the brush core. I’ll explain this in detail later.

In Wei Dan’s “Brush Methods,” the innermost part of a brush head is called the center. The brush hair outside the center is the secondary hair. This first layer of secondary hair is called the “core protector” (this is the Japanese term; Wei Dan himself didn’t name it). The center plus the secondary hair (core protector) together form the brush core.

“Zhang Zhi… was skilled in clerical, running, and cursive scripts, and also excellent at making brushes. Seeing Cai Yong’s ‘Brush Momentum,’ he wrote ‘Brush Core’ in five parts.”

Zhang Zhi’s Chinese brushes haven’t survived, but historical records show he had theories about brush cores. In the Yuan Dynasty, Zheng Shao’s “Yan Ji” article, in Liu Youding’s notes, it says: “Zhang Zhi… was skilled in clerical, running, and cursive scripts, and also excellent at making brushes. Seeing Cai Yong’s ‘Brush Momentum,’ he wrote ‘Brush Core’ in five parts.” Zhang Zhi was excellent at making brushes. After seeing Cai Yong’s “Brush Momentum” article, he wrote “Brush Core” in five parts. People who understand calligraphy actually understand how to use the brush core. People who make good Chinese brushes actually make good brush cores.

“Better for the core to be small than large – this is the essential principle of brush making.”

Note that Wei Dan said in his “Brush Methods” article: “Better for the core to be small than large – this is the essential principle of brush making.” This means that when making Chinese brushes, the most important thing is for the core to be small, not large. Better small than large – this is the secret of making brush cores, which unfortunately many people have forgotten. A small brush core makes the brush tip easily sharp.

What Are the Three Secondary Layers?

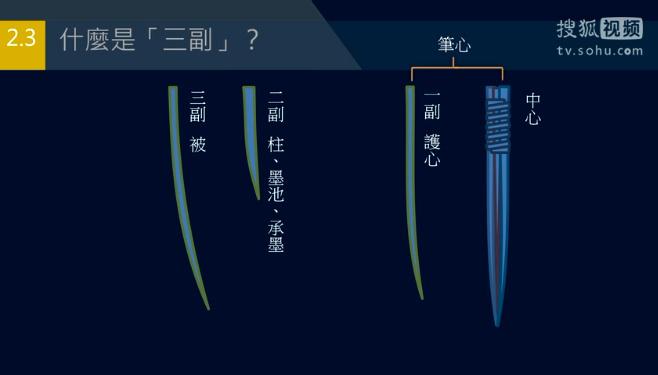

Diagram of the three-secondary brush structure

The first secondary layer has been explained – it’s the secondary hair outside the center. The second secondary layer is also called the “brush column,” “ink pool,” or “ink holder” – these are names Wei Dan established. The third secondary layer is the outermost layer, anciently called the “cover,” like the blanket we cover ourselves with when sleeping. However, these names differ somewhat between ancient and modern times, and between China and Japan. These are the three secondary layers.

Diagram of the three-secondary brush structure

So the entire brush head structure emerges. The center plus the first secondary layer form the brush core. Adding the brush column makes the second secondary layer. Wrapping another layer of cover hair on the outside makes the third secondary layer. The second secondary layer is particularly short, creating a gap with the third secondary layer – that’s the yellow part shown. This hollow space is where ink is stored, which is why the second secondary layer is called the “ink pool.”

“The Xuan people, Zhuge Gao, guard the family business without loss.”

Now when you read Ouyang Xiu’s poetry, you should understand what he’s talking about. In Ouyang Xiu’s poem “Shenyu Hui Xuanzhou Bi Xi Shu,” he says: “The Xuan people, Zhuge Gao, guard the family business without loss.” Xuan people refers to people from Xuanzhou, Anhui. Zhuge Gao was a famous brush maker whose family had been making brushes for generations and was very renowned. “Tightly bind the core with long hair, three secondary layers quite precise.” Long hair was made into the center, bound very tightly, then three secondary layers were added outside, very precisely. “Hardness and softness suit the hand, a hundred brushes differ not by one.” The degree of hardness and softness was just right for the hand – making a hundred brushes, each one was the same. This was industrial production standards.

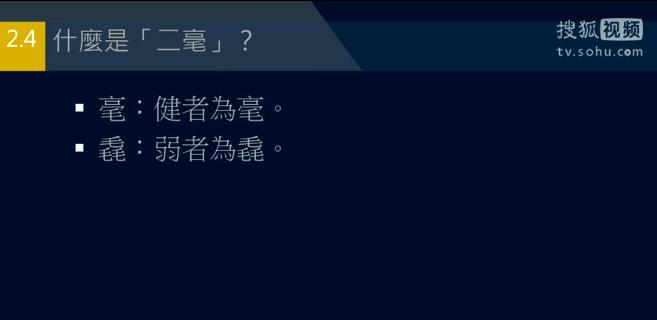

Hao: Strong hair is called “hao”

Cui: Weak hair is called “cui”

Two Types of Brush Hair

Brush hair is divided into two types. Strong hair is called “hao” (毫), weak hair is called “cui” (毳). This character is three “hair” characters stacked together, pronounced like “jade.” Cui refers to short hair, weak hair, soft hair. Good Chinese brushes use both types of hair – one hard, one soft, matched together. Pure hard or pure soft brushes are not good Chinese brushes. (Qi Ming note: This is Teacher Huang Jian’s personal opinion. Many calligraphy enthusiasts with special brush preferences might prefer pure hair brushes.)

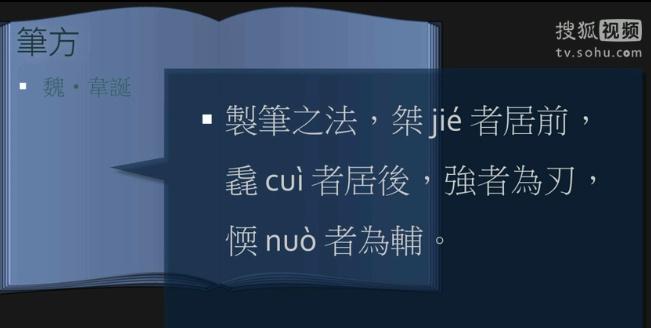

“The method of making brushes: place the strong ones in front, the soft ones behind. The strong serve as the blade, the weak as support.”

Wei Dan said: “The method of making brushes: place the strong ones in front, the soft ones behind. The strong serve as the blade, the weak as support.” Strong hair means stiff hair, cui means soft hair. Stiff hair goes in front, soft hair goes behind, near the brush root. Strong hair serves as a blade, weak hair provides support.

What we commonly call “rabbit hair” refers to hair from wild rabbit backs.

The ancients believed the best stiff hair came from wild rabbits. What we commonly call “rabbit hair” refers to hair from wild rabbit backs. It must be from autumn, preferably hair newly grown in the eighth lunar month – that’s the best. (Qi Ming note: At this time, wild rabbits grow new fur to prepare for the cold winter, so wild rabbit hair at this time is the best.)

But note that rabbit hair comes in several types. The highest grade is purple.

But note that rabbit hair comes in several types. The highest grade is purple, so we call it “purple hair.” There’s also mixed-color rabbit hair, like black-tipped rabbit hair, which has more varied colors.

Different parts of a sheep’s body produce hair of different quality.

The most commonly used soft hair is sheep hair. Different parts of a sheep’s body produce hair of different quality. Sheep hair from Huzhou, Zhejiang is very suitable for making Chinese brushes.

This shows selected, unprocessed sheep hair that can be made into Chinese brushes. (Qi Ming note: If you’re interested, you can check out my Sina blog article “Visiting Wenggang on May 1st to See Chinese Brushes – Truly the Capital of Chinese Brushes,” which has many photos I took of brush-making scenes in Wenggang.)

Using one hard and one soft type of hair to make brushes is called “mixed hair brushes.”

In Summary

Using one hard and one soft type of hair to make brushes is called “mixed hair brushes.”

After the Song Dynasty: Scattered Excellent Brush

Were Wei Dan’s brushes good? Of course! Even until the late Qing Dynasty, nobles still used this type of layered brush. But Wei Dan brushes were complex to make and costly. As a result, by the Song Dynasty, a simplified brush called the “scattered excellent brush” became popular.

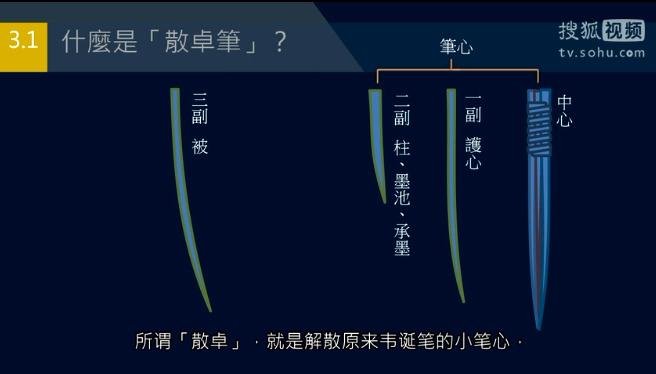

“Scattered excellent” means dissolving the small brush core of the original Wei Dan brush.

What is a “Scattered Excellent Brush”?

“Scattered excellent” means dissolving the small brush core of the original Wei Dan brush, mixing the center’s stiff hair with the first and second secondary layers’ soft hair together to form a large brush core. This eliminated the second secondary layer – the ink pool – so scattered excellent brushes have no ink pool function. Then another layer of secondary hair is added outside the large brush core, completing the brush head construction.

In summary: the scattered excellent brush structure is one core, one secondary layer – large core, thin cover.

In summary: The scattered excellent brush structure is one core, one secondary layer – large core, thin cover. This type of brush was much simpler to manufacture. At that time, Su Dongpo and Huang Shangu both began experimenting with scattered excellent brushes. Most Chinese brushes sold in the market today are scattered excellent brushes.

Expanded Range of Hair Types

After the Song Dynasty, the range of hair types gradually expanded, no longer limited mainly to rabbit hair and sheep hair. (Qi Ming note: Actually in the Song Dynasty, Su Shi and Huang Tingjian had different brush preferences. Su Shi was more traditional, preferring short-tipped old-style core brushes for daily use, while Huang Tingjian liked new-style long-tipped scattered excellent brushes. Looking at these two calligraphers’ works, we can see that Su Shi’s surviving calligraphy works are generally smaller, while Huang Tingjian has many large-scale works.)

Hair for wolf hair brushes comes from weasel tails.

For example, wolf hair. Wolf hair was actually used for brushes in the Qin and Han dynasties, but its stiffness doesn’t match rabbit hair. Note that “wolf” doesn’t mean the big gray wolf, but the small weasel. Hair for wolf hair brushes comes from weasel tails. Now we often see “True Winter Northern Wolf Hair” carved on wolf hair brush handles, meaning winter hair from northern weasels. (Qi Ming note: I strongly recommend reading this article: “How to Identify Real and Fake Wolf Hair Brushes (Only Discussing Pure Wolf Hair Brushes)”)

Mountain horse isn’t a horse but a water deer – essentially deer hair.

Mountain horse – we often see mountain horse brushes now. Mountain horse isn’t a horse but a water deer – essentially deer hair. Mountain horse brushes are very common in Japan. Ancient China also used deer hair, but it’s not common in modern times.

Stone badger

Stone badger – the stone badger is a small animal found throughout Eurasia, living in northern regions. Since weasels are now quite rare, stone badger hair is used more often.

Stone badger hair’s stiffness is close to wolf hair.

Stone badger hair’s stiffness is close to wolf hair. Both Japan and mainland China produce stone badger brushes.

Hard hair brushes: Like pure wolf hair brushes, very stiff.

Soft hair brushes: Like pure sheep hair brushes and chicken feather brushes – very soft.

Mixed hair brushes: Appropriate hardness and softness, most useful.

In Summary

Chinese brushes can be divided into three types based on their hair:

Hard hair brushes: Like pure wolf hair brushes, very stiff. Great for painting orchids and bamboo, but often feels too stiff for writing.

Soft hair brushes: Like pure sheep hair brushes and chicken feather brushes – very soft. The most common is pure sheep hair brushes, which are relatively soft but can have very long tips and work well for large brushes. Pure sheep hair and pure wolf hair brushes use the same hair type for both core and secondary layers. In Wei Dan brushes, sheep hair was only used for secondary layers, not the center. Pure sheep hair brushes became popular quite late, only becoming common in the Ming and Qing dynasties.

For usefulness, I personally think mixed hair brushes with appropriate hardness and softness are still best.

Key Points of This Section

- Four types in Chinese brush development history

- Wei Dan: Core Three-Secondary Two-Hair Brush

- Scattered Excellent Brush

Discussion Questions

- For calligraphy Chinese brushes, the key is having a brush core. How do Wei Dan and scattered excellent brush cores differ?

- Would you want to buy Wei Dan brushes or scattered excellent brushes? Or buy both types to experiment?