In a previous article about China’s top five ink brands and common ink characteristics, I briefly mentioned the difference between oil soot ink and pine soot ink. However, I didn’t go into detail about the ink-making process. If you’ve ever wondered how ancient Chinese ink was made, this article will answer all your questions. Today, let’s take a deeper look at the traditional methods used to create ink sticks in ancient times. After reading this, you’ll fully understand what makes oil soot ink different from pine soot ink and appreciate the craftsmanship behind this essential calligraphy supply.

How Ancient Chinese Ink Was Made?

Chinese calligraphy requires ink, and the quality of ink greatly affects the final artwork. Besides water, what other ingredients go into making ink?

During the Ming Dynasty, Song Yingxing wrote in his famous book “Tian Gong Kai Wu” (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature): “All ink is made by burning materials to create soot, then solidifying it with a binding agent.” Burning materials refers to burning wood or oil to produce carbon powder, also called soot or lampblack—essentially carbon black that creates the dark color. The binding agent is usually animal glue. In other words, carbon black, glue, and water are the three main components of ink.

Understanding Carbon Black

Let’s talk about carbon black first. When wood burns without enough oxygen, it produces thick smoke, and these smoke particles are carbon black. Carbon exists in nature in three forms: diamond, graphite, and coal. Carbon black is carbon in a fine, shapeless powder form. As a widely used black pigment, it’s extremely stable and has powerful covering ability.

Qi Ming’s tip: This is why ink stains on clothes are so hard to wash out. If you accidentally get ink on your clothes, wash it immediately while it’s still wet and scrub vigorously—don’t wait for it to dry!

Natural Carbon Black

Before people learned how to make carbon black, ancient Chinese used graphite. Graphite is natural carbon that’s relatively soft and easy to grind into powder. Lu Yun of the Jin Dynasty wrote to his brother Lu Ji, mentioning that “Cao Gong (Cao Cao) stored hundreds of thousands of pounds of graphite.” This shows that even during the Wei and Jin periods, people still used graphite for writing.

In the early Ming Dynasty, Tao Zongyi wrote in “Nancun Chuogeng Lu”: In ancient times, people didn’t have ink. They used small bamboo sticks dipped in lacquer to write. Later, they learned to grind stones together to create black liquid.

Early Inkstones and Grinding Stones

This is a Han Dynasty inkstone, quite simple in design. Unlike modern inkstones, it came with a separate grinding stone. People would place a bit of graphite or soot powder on the inkstone, add water, and press down with the grinding stone to create liquid ink.

The Invention of Ink Pellets

Tao Zongyi also wrote: “During the Wei and Jin periods, ink pellets were first created by mixing lacquer soot and pine soot together.” Based on archaeological discoveries, ink pellets were actually used much earlier. Mixing lacquer soot and pine soot together shows that people had already learned to use glue as a binding agent.

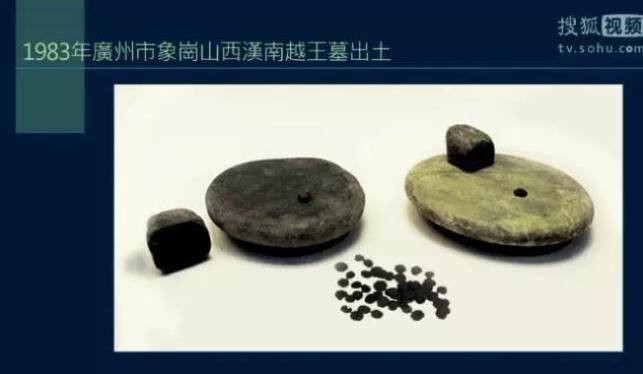

Ink from the Han Dynasty

In 1983, three inkstones were discovered in the Western Han tomb of the King of Nanyue at Xianggang Mountain in Guangzhou. Here are two of them. The tomb also contained 4,300 ink pellets. In 1973, Shanxi Province uncovered stone inkstones and ink pellets dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period—very ancient indeed.

People would place several ink pellets on the inkstone with water and grind them to make liquid ink. It’s interesting to imagine that Confucius, Laozi, and Zhuangzi probably used similar methods.

What’s the Difference Between Oil Soot Ink and Pine Soot Ink?

Burning Pine Wood for Soot

Later, people mastered the technique of burning wood to collect soot, which produced higher quality carbon powder. From the Eastern Han Dynasty until the Ming Dynasty, pine soot was the main raw material for making ink.

According to Song Yingxing’s “Tian Gong Kai Wu,” during his time, “nine out of ten ink makers used pine soot.” It had become the dominant method.

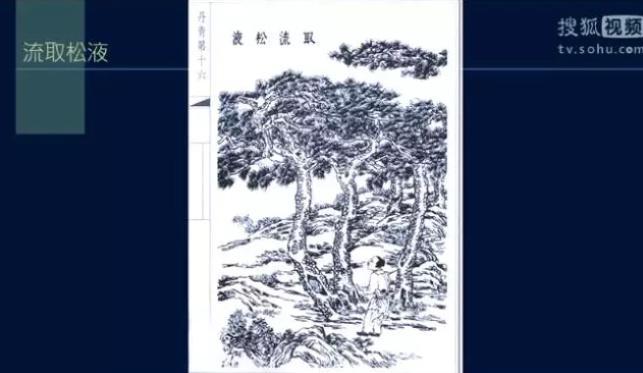

Pine soot comes from burning pine trees. Before cutting down the tree, workers first had to drain the resin (pine rosin) from it. If the resin wasn’t removed, the resulting soot would have adhesive problems.

Draining Pine Resin

The method for draining pine resin wasn’t complicated. Workers would carve a small hole at the base of the pine tree and place a small lamp inside to slowly heat it. The tree’s resin would gradually flow out.

Collecting Pine Soot

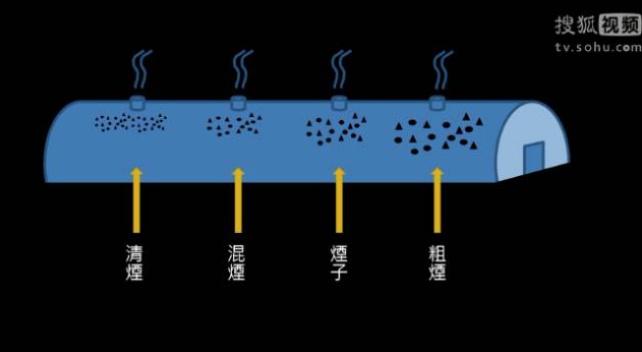

The pine wood was then placed in a kiln and set on fire. These kilns stretched over thirty feet long. From beginning to end, small openings were set in the ceiling. Soot particles would collect on the inner walls, while excess smoke escaped through the small openings.

According to “Tian Gong Kai Wu,” the kiln fire burned for several days. After the fire was extinguished and the kiln cooled, workers could enter to scrape off the carbon black. The soot from the farthest section was called “clear soot”—this was the raw material for making premium ink.

Qi Ming’s note: Yi De Ge’s “Yun Tou Yan” (Cloud Head Glory) ink gets its name from this. I believe “Cloud Head” symbolizes distance—the farther into the kiln, the finer the soot quality. The closer to the kiln entrance, the coarser the quality. “Yan” (Glory) probably refers to the ink’s rich black color.

The middle section was called “mixed soot,” suitable only for making ordinary ink. The coarse soot scraped from near the entrance, after being processed and refined, could be used for woodblock printing. The coarse soot closest to the door could only be used for paint and coating.

How Oil Soot Is Made

Besides burning pine wood, people could also burn oil to collect soot. But what kind of oil?

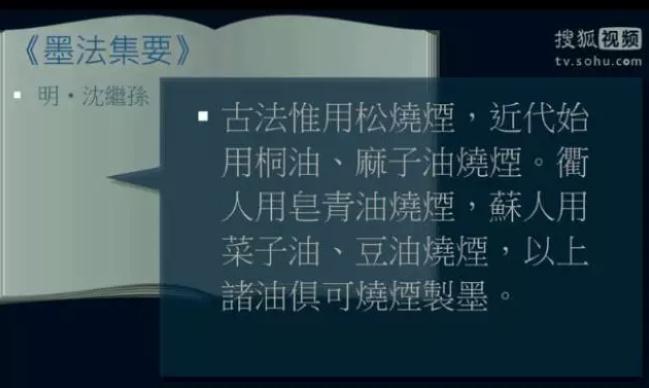

During the Ming Dynasty, a Suzhou scholar named Shen Jisun learned to make ink himself. He wrote a book called “Mo Fa Ji Yao” (Essential Methods of Ink Making), which recorded: The common oils burned during the Ming Dynasty were tung oil, hemp seed oil, Chinese honey locust oil, rapeseed oil, and soybean oil. Actually, people also used pork lard and lacquer oil.

He further explained: “However, tung oil produces the most soot. Ink made from it is black and shiny, becoming darker with age. Other oils produce less soot, making ink that’s light and dull, becoming lighter with age.” Tung oil soot was cost-effective and produced excellent results.

The Oil Soot Collection Method

According to the illustrations in “Tian Gong Kai Wu,” burning oil to collect soot was similar to lighting ancient oil lamps. The oil lamp sat on a stand below, with a board placed above it. Gradually the board would turn black, and the carbon black could be scraped off. One pound of tung oil could produce about one ounce of carbon black.

Collecting Soot with Bowls

However, using boards to collect soot wasn’t very efficient. An improved method used bowls or ceramic basins. Oil was burned below while the vessel above collected the soot.

Japanese Oil Soot Method

The Japanese method of burning oil for soot was similar to China’s. An oil vessel burned below while a lid above collected the soot. The oil soot method was simpler than pine soot, making oil soot very popular during the Qing Dynasty.

Modern Industrial Carbon Black

Modern industry uses industrial carbon black extensively—in car tires, batteries, and more. Production methods vary, using natural gas, acetylene, or petroleum residue as raw materials. These can use decomposition methods that don’t necessarily require burning. Many ink products on the market today are made with industrial carbon black.

We’ll discuss modern ink-making techniques in a future article. I also recommend reading our article “For Calligraphy Practice: Should You Use Liquid Ink or Grind Your Own?”

This article is based on notes from “Huang Jian’s Basic Calligraphy Course,” Lesson 11: “Understanding Ink (Part 1).” Qi Ming will continue organizing more notes from this series, so please stay tuned.

Footnote:

① “Tian Gong Kai Wu” (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature)

First published in 1637 (10th year of Chongzhen, Ming Dynasty), this three-volume, eighteen-chapter work covers agriculture and handicrafts, including mechanics, bricks and tiles, ceramics, sulfur, candles, paper, weapons, gunpowder, textiles, dyeing, salt production, coal mining, and oil pressing.

“Tian Gong Kai Wu” is the world’s first comprehensive work on agricultural and handicraft production. It’s a comprehensive scientific and technological work from ancient China, sometimes called an encyclopedia. The author was Ming Dynasty scientist Song Yingxing. Foreign scholars call it “China’s 17th-century encyclopedia of technology.”

If you’re interested, you can borrow it from the library—it’s a fascinating read!