Today, we will learn about how traditional Chinese brushes are made through this article.I once published an article on my blog titled “Visiting Wengang During May Day Holiday to See Chinese Brushes – Truly the Capital of Chinese Brushes.” In that article, I detailed everything I saw and experienced in Wengang during the May Day holiday, including a series of photos I took of the Chinese brush making process at Master Li Xiaoping’s workshop at Chun’an Hall.

To be honest, I’ve been using Chinese brushes to practice calligraphy since I was little, but seeing the actual brush-making process with my own eyes was a first for me. I was truly shocked by how complex the process is. You need to understand that the bristles in the Chinese brushes we use are almost all hand-selected by master craftsmen, examining each hair individually with their naked eyes.

In Huang Jian’s Basic Calligraphy Tutorial series, Master Huang Jian dedicated an entire episode to explaining the Chinese brush making process. Let’s take a look together.

How Traditional Chinese Brushes Are Made?

Many ancient calligraphers made their own Chinese brushes, including Wei Dan, Zhang Zhi, Wang Xizhi, Zhiyong, and others. For calligraphers, a Chinese brush is like a warrior’s sword – it must be perfect. But nowadays, many people have never seen how a Chinese brush is actually made. If you understand a bit about the Chinese brush making process, it will definitely help you choose better brushes in the future.

Preparing Hair Materials

4.1 Preparing Materials – Water Basin Work

The first step is preparing materials – getting the brush hair ready. In China, hair selection is done in water basins, which requires very detailed work.

Preparing Hair Materials

For water basin work, besides a basin of water, the main tool is a bone comb. Usually made from cow shoulder blade bone, it can comb through the bristles and also be used to align the hair roots.

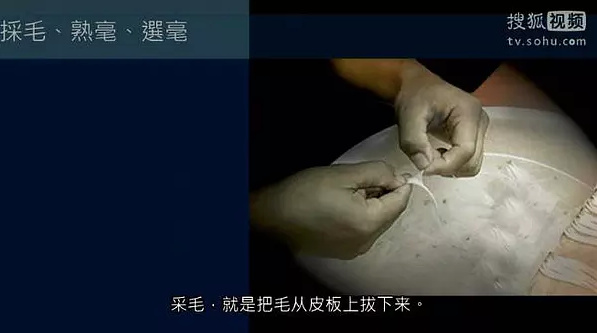

Hair harvesting means pulling the hair from animal pelts. Then the bristles are soaked in lime water to remove oils and odors, while also disinfecting them. This step is called “curing the bristles.” (Qi Ming’s Note: The soaking time in lime water needs to be controlled very carefully. If soaked too long, it will shorten the lifespan of the hair material.)

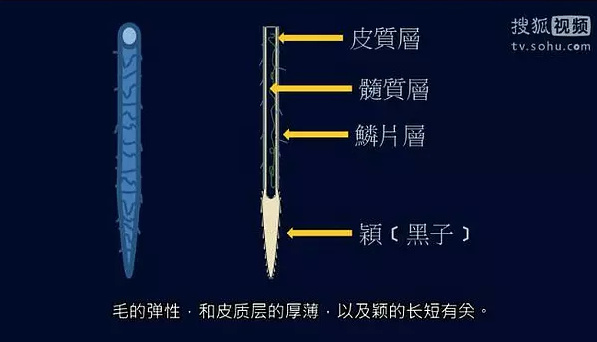

The hair’s elasticity is related to the thickness of the cuticle layer and the length of the tip.

The third step is crucial and is called “hair selection” – sorting the hair into different grades. Each hair is like a small pouch with three layers. The pouch itself is the cuticle layer. Inside the pouch is the medulla, which is fibrous – this is the medulla layer. On the outside of the pouch are scales, called the scale layer. The solid part at the hair tip is called the “ying,” which professionals call the “black tip.” The hair’s elasticity relates to the thickness of the cuticle layer and the length of the tip.

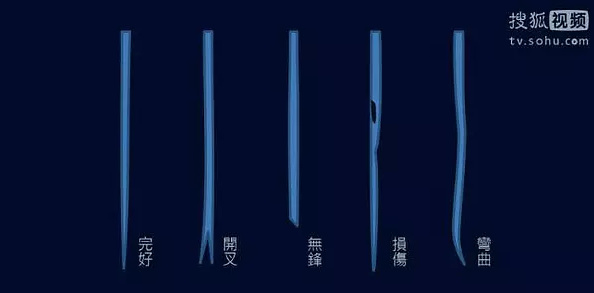

Different grades of hair

Truly perfect hair is round and straight – only about 3-5 hairs out of every 100. The others usually have defects, such as split ends, no sharp point, damaged or bent hair shafts, etc. During hair selection, craftsmen repeatedly comb and wash in water basins, picking through each hair individually, removing defective ones, then sorting by color, hardness, length, and thickness. This is extremely precise craftsmanship.

According to experts, usable brush hair from one sheep amounts to only about four taels (traditional Chinese weight unit), with less than 1.6 taels having “black tips.” A skilled hair-sorting master can divide these four taels of brush material into ten different grades based on length, thickness, and hardness, for use in various parts of the Chinese brush.

Tang Dynasty poet Bai Juyi wrote a poem called “Purple Hair Brush”: “In Jiangnan, on rocks, lives an old rabbit, eating bamboo and drinking spring water, growing purple hair; People of Xuancheng collect it for brushes, selecting one hair from millions.” This captures the difficulty of hair selection.

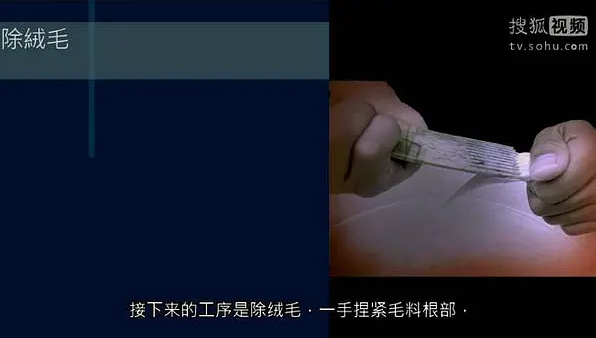

Removing down hair

The next process is removing down hair. Hold the hair material firmly at the root with one hand, and comb with the bone comb using the other hand to remove the down. Each hair has three layers – the so-called down hair refers to the outermost scale layer.

Scales on the hair shaft

Under a microscope, you can see that the hair shaft’s outer wall isn’t smooth but scale-like. Chinese brushes can hold ink because these scales prevent the ink from flowing down immediately. After combing, some of these scales will be removed. But note that if all scales fall off, the hair shaft becomes completely smooth and can’t hold ink – the flow will be very fast. So there can’t be too many scales, but there can’t be none either. When you buy a Chinese brush, don’t keep combing it all the time.

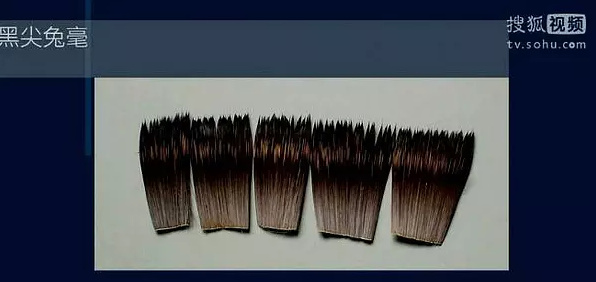

Black-tipped rabbit bristles

These are selected rabbit hairs – black-tipped rabbit bristles.

Sheep bristles

These are selected sheep bristles.

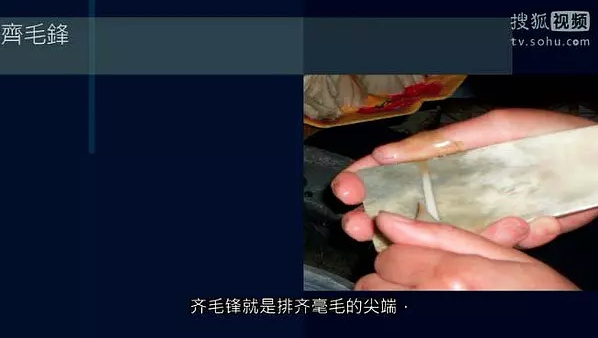

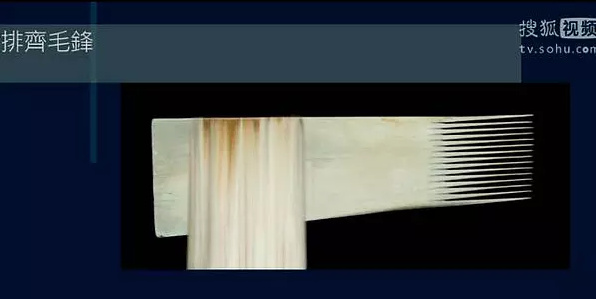

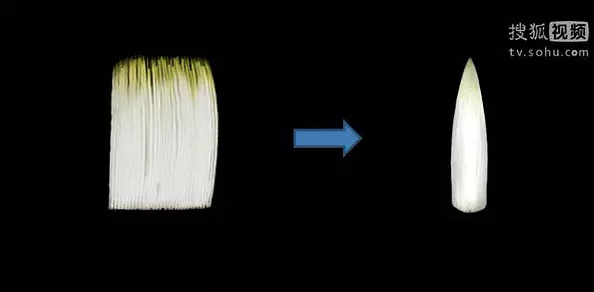

Aligning hair tips means arranging the bristle tips evenly.

The next process is aligning the hair tips. This means arranging the bristle tips evenly. Align the hair against one edge of the bone comb, press down on the tips with one hand, and gently pull back with the other hand. Repeat this process to arrange the hair tips neatly.

Aligning hair tips

Bristles have two ends – one is the sharp tip. When the tips are aligned into a sheet, the other end of the bristles (the hair base) is still uneven.

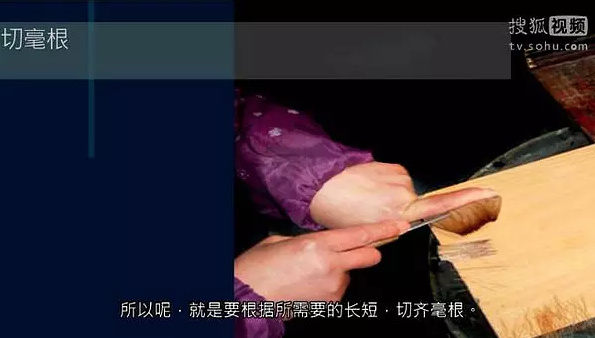

Cut the hair roots to the required length.

So you need to cut the hair roots to the required length. This way, every bristle becomes the same length.

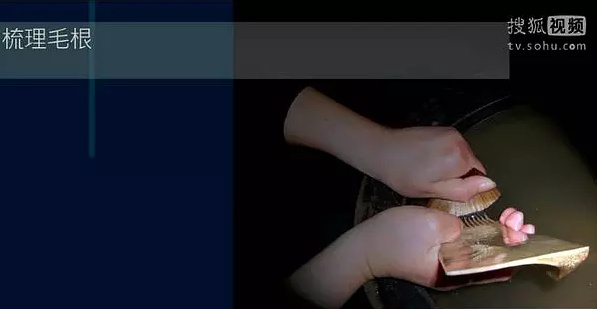

Combing the hair roots

After cutting the hair roots, hold the tip section with one hand and use the bone comb with the other to comb through the hair roots, removing any broken or fragmented hairs inside.

4.2 Mixing Materials

Combining different types of hair together – this is called mixing materials.

After preparing the hair material, you need to mix different types. You must decide what kind of Chinese brush you want to make – soft or hard, long or short, what it’s for, what kind of writing – and combine various hairs accordingly. This is called mixing materials. (Qi Ming’s Note: For example, the material ratio for Qi Ming’s custom Qingquan Chinese brush is: 85% sheep hair, 12% pig bristles, 3% nylon. Combined together, the brush has moderate softness and hardness, very suitable for writing, and can easily create many delicate strokes.)

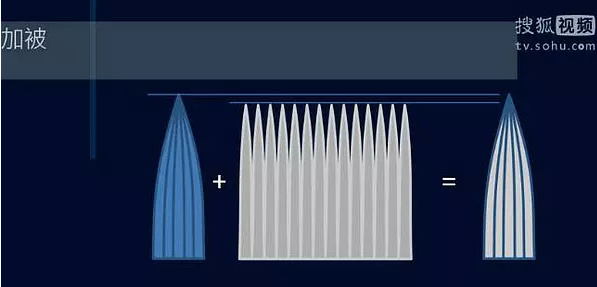

Material mixing mainly divides into two parts: primary bristles for the brush core should include some harder hair, while secondary bristles for the covering don’t need to be as hard.

First use dozens of fine human hairs, mixed with blue sheep hair and rabbit down (note: rabbit hair that is long and strong is called bristles; short and weak is called down), making sure they are evenly aligned.

Don’t use too many different types of hair – usually two to four types. There’s a historical text, supposedly written by Wang Xizhi but actually not, called “Brush Manual.” The “Brush Manual” mentions secondary bristle combinations: “First use dozens of fine human hairs, mixed with blue-green sheep hair and rabbit down.” There’s a note here: “Rabbit hair that’s long and strong is called bristles; short and weak is called down.” Make sure they’re evenly aligned – you can see this formula uses three types of hair: fine human hair, blue-green sheep hair, and rabbit down.

The Chinese brush used by Mr. Sha Menghai

The Chinese brushes used by Hangzhou’s Sha Menghai included some pig bristles in the brush core along with short hair. Pig bristles are hard and thick and can’t be used alone for brushes. Split them into four strands and insert into the brush core to increase elasticity.

Used fine smooth tips, coarse smooth tips, and aged smooth tips as main materials, then added small amounts of raccoon dog needle hair, with fiber and pig bristles as padding.

The Chinese brush used by Master Qigong at age 86 had quite a variety of hair materials. According to Li Zhaozhi’s book “Qigong and Brush Craftsmen”: “First use fine smooth tips, coarse smooth tips, and old smooth tips as main materials (these three are sheep bristles of different thicknesses), then add small amounts of raccoon dog needle hair, with Chinese mallow fiber and pig bristles as padding.” This combines sheep bristles, raccoon dog needle hair, Chinese mallow fiber, and pig bristles – four types of hair total.

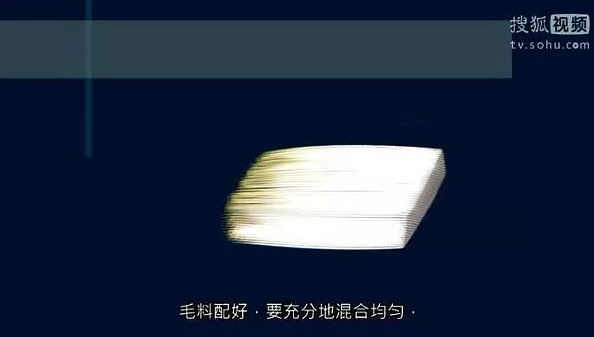

Once the hair materials are mixed, they must be thoroughly and evenly blended.

Once the hair materials are mixed, they must be thoroughly and evenly blended.

Once the hair materials are mixed, they must be thoroughly and evenly blended. These are sheep bristle sheets with roots cut and materials mixed. The preparatory work for making Chinese brushes is now mostly complete.

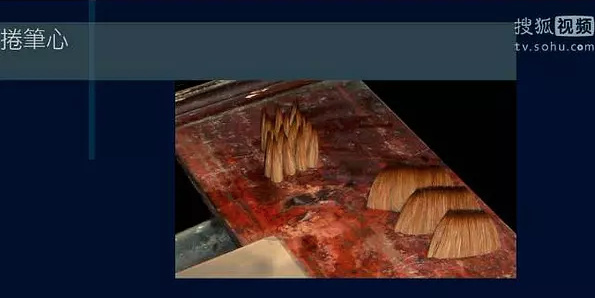

4.3 Rolling the Brush Core and Adding Covering

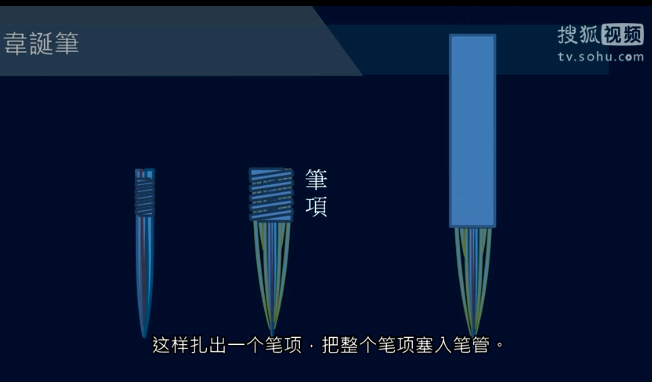

With materials ready, we officially begin making the brush head. For scatter-tip brushes (Qi Ming’s Note: For information about scatter-tip brushes, please refer to another article on Qi Ming’s calligraphy blog: “What Were Ancient Chinese Brushes Like? Do You Use Core Brushes or Scatter-tip Brushes?”), the brush head has only two parts: the core and the covering.

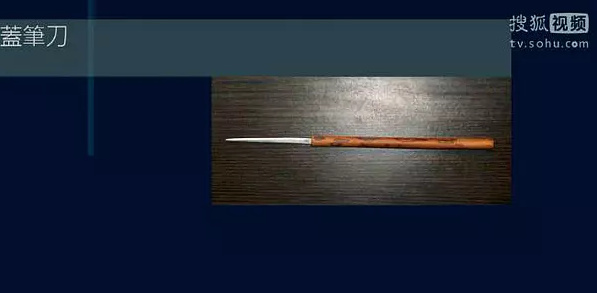

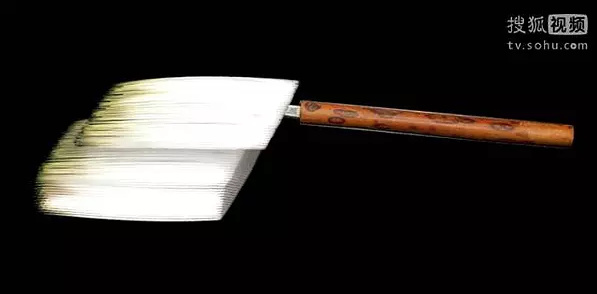

Brush knife

This requires a tool called a brush knife.

Brush knife

Look at this diagram – use the brush knife to pick out a needed layer of hair sheet.

Then roll this hair sheet up, and one brush core is complete.

These are wolf hair sheets and the finished rolled brush head.

Then add the covering. In scatter-tip brushes, the covering is just a thin layer of hair material, mostly single-type hair without mixing other hairs. The covering hair is long, usually just a bit shorter than the brush core. Let me introduce Hu brushes here – they not only align the brush tips but actually align the hair tips. This is a very distinctive manufacturing technique. The covering both protects the brush core and has a润色 (decorative) effect.

Note that when brush craftsmen pick each layer of hair, no matter how experienced they are, there will always be slight differences in amount.

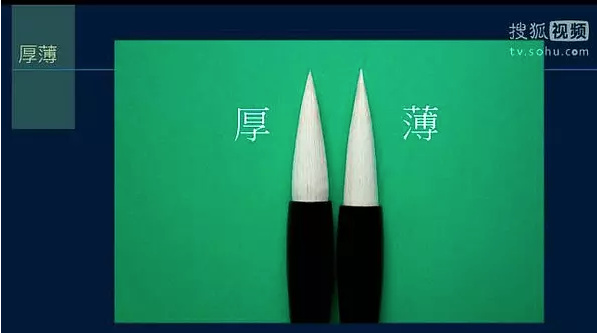

These are from the same batch of brushes I had custom made. You can see the left brush head is fuller, while the right one is thinner. When buying Chinese brushes, you should compare several brushes – thicker ones work better than thinner ones. (Qi Ming’s Note: Regarding “thicker works better than thinner,” I feel this can’t be generalized – it depends on each person’s brush-using habits.)

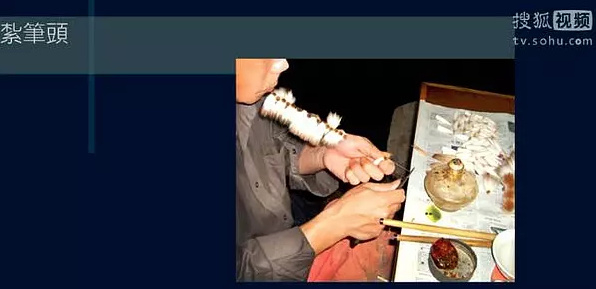

4.4 Binding the Brush Head

Once the brush head is made, wait for it to dry completely, then tie it tight with thread. If the brush hair isn’t dry and is still wet inside, the Chinese brush will eventually mold and break. The hardest part of this step is making sure the bound brush head is perfectly round. So when binding, apply force evenly – any uneven pressure will cause deformation.

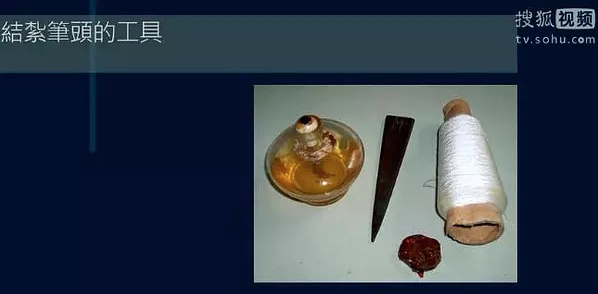

Tools for binding brush heads, from left to right: alcohol lamp, brush ruler, rosin, waxed thread.

The alcohol lamp melts the rosin. Why use rosin? To keep the brush head base flat – coating with rosin fixes the hair roots.

I’ve taken apart many brush heads for research to see how many times masters actually bind them. Usually it’s two rounds, sometimes three, and large brushes get four rounds.

The hair in the center of a Chinese brush is called “life hair” in Japanese. If a few secondary bristles from the outer layer fall out, it’s not a big problem – there’s still life. But if even one life hair falls out, disaster begins, because it will keep falling until there’s no life left.

So Tang Dynasty master calligrapher Liu Gongquan said: “If you bind the brush head extremely tight and one hair comes out, it’s immediately unusable.” Once you lose one, it starts to loosen.

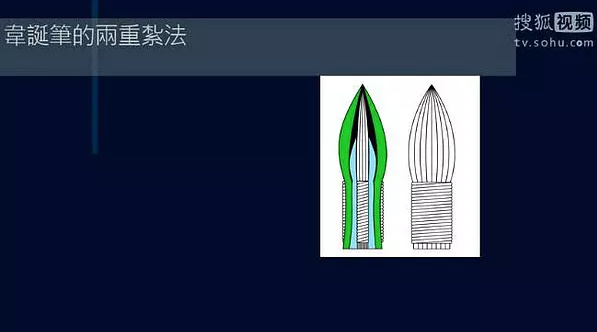

According to Wei Yan’s “Brush Methods,” when Wei Dan made brushes, the brush core was bound once first, then bound again after adding secondary bristles – so inside and outside were bound twice. Binding twice wasn’t enough – each binding had many rounds, creating a “brush neck.” The “neck” originally means the back part of the head and neck. The back of the brush head should be bound to create a neck section – this naturally prevents hair loss.

I really hope craftsmen can bind more rounds, preferably like Wei Dan’s brushes – bind the core once, then bind again after adding covering. I think that would be much safer.

5. Brush Handles

Now let’s talk about brush handles. Brush handles are also complex – I can only briefly discuss them here.

5.1 Materials

First, brush handle materials. Ancient brush handles were made of bamboo or wood. During the Warring States and Qin-Han periods, some brushes used wooden handles, possibly because the north had more wood and less bamboo. Historical records say Meng Tian invented brushes using wooden handles too. Using bamboo is called “brush tube.” After the Wei and Jin dynasties, basically everyone used tubes.

Ming Dynasty writer Wen Zhenheng (great-grandson of Wen Zhengming) said in “Treatise on Superfluous Things” about brushes: “Ancient times had gold and silver tubes, ivory tubes, tortoiseshell tubes, glass tubes, engraved gold and green sandalwood tubes, and recently purple sandalwood carved flower tubes – all vulgar and unusable. Only spotted bamboo tubes are elegant, otherwise just use white bamboo.” This passage discusses elegance versus vulgarity – basically taste. Bamboo represents the gentleman’s virtue, is inexpensive and high-quality. Ancient scholars basically all used bamboo tubes for their brushes.

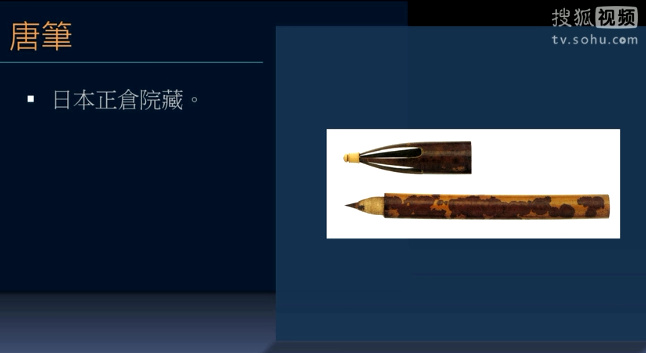

Spotted bamboo is also called Xiang Concubine bamboo, with dark spots on the bamboo shaft. Japan’s Shosoin treasury contains several Chinese Tang Dynasty brushes, and Japanese-made ancient brushes also mostly use spotted bamboo.

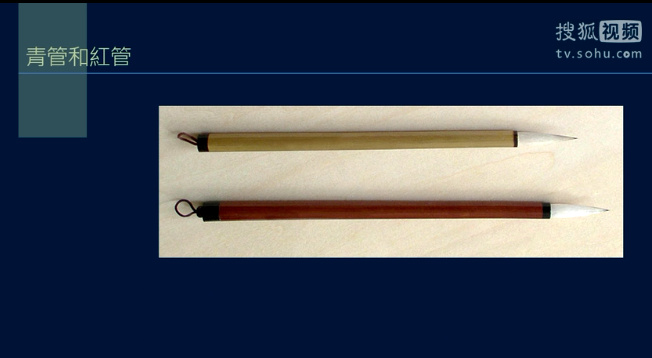

Currently on the market there are commonly blue tubes and red tubes – red tubes are dyed. The Book of Songs’ “Quiet Girl” chapter has “The quiet girl is lovely, she gave me a red tube.” Red tubes are red-colored tubes. In ancient times, female historians in the imperial palace, Han Dynasty secretaries, and court officials all used red tubes. [Qi Ming’s Note: Regarding the “red tube” mentioned here, there’s no definitive explanation currently. One theory says red-handled brushes, another says it’s the same as “ti” (white cogongrass, early stage cogongrass, symbolizing marriage). Some plants are red when first growing or just sprouted – not only bright in color, some are even edible. But it could also refer to red-colored tubular musical instruments, etc.]

5.2 Thickness

Now let’s discuss brush handle thickness. Why were Warring States and Qin-Han brushes so small and thin? Two reasons: First, brush heads were small then, with few layers, sometimes no layering at all. Second, people habitually stuck brushes in their hair, so handles were very thin.

Ancient people had hair buns where they could stick brushes. Later, as brush heads got bigger and handles thicker, this habit gradually disappeared.

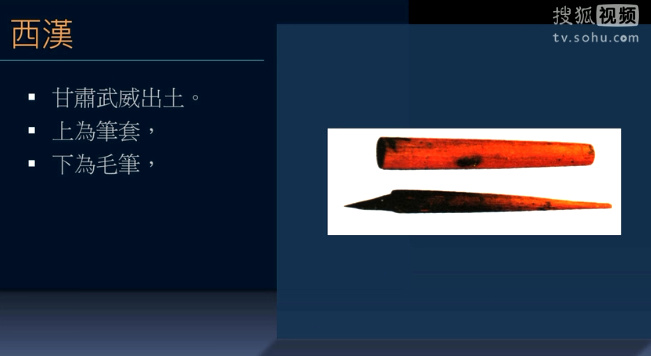

This is an excavated Western Han Chinese brush. The brush head had grown larger and the handle was relatively thicker. But one end was still sharpened for easy insertion into hair buns. After Han Dynasty masters Zhang Zhi and Wei Dan, true calligraphy brushes appeared, and people gradually began using hollow bamboo tubes.

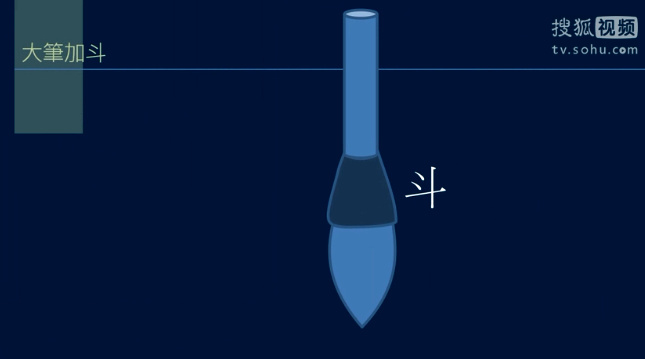

Bamboo tubes have one problem – when they’re thick, they’re hard to grip. If the brush head is very large, you need to add a ferrule rather than use one big bamboo tube.

Speaking of this, Qi Ming also wants to explain to everyone why Qi Ming’s custom Qingmei Chinese brush doesn’t use only bamboo tubes like the Qingquan Chinese brush does. This is because the Qingquan brush (old jade bamboo version) can only handle brush heads up to a certain maximum diameter. If it were any bigger, we’d need larger bamboo, but that would inevitably make the handle too thick to grip comfortably.

This is Qi Ming’s custom Qingquan Chinese brush, without ferrule

Look at the middle brush – the tube is very thick, with a hollow space larger than the brush head diameter. So a smaller black tube is installed in front to hold the brush head. A true ferrule brush is the bottom one – the handle isn’t thick, but because it has a ferrule, it can install very large brush heads.

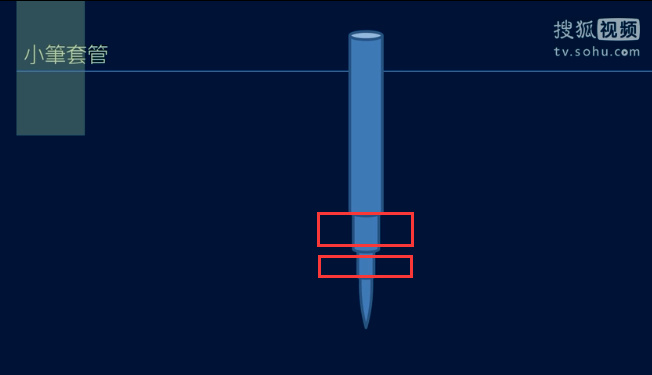

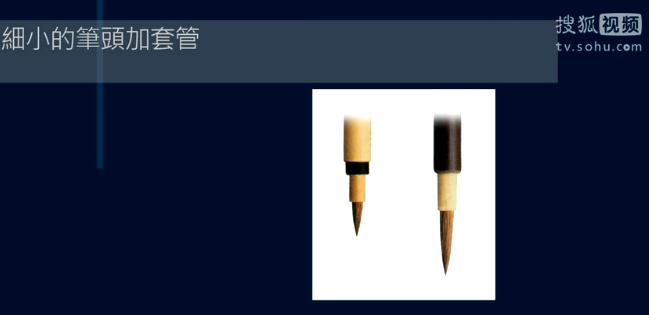

If the brush head is very small, you don’t make the handle extremely thin all the way through, but use sleeve tubes – sometimes several layers of sleeves. The advantage of adding sleeve tubes is that the part of the handle you grip doesn’t need to be made very thin.

Here’s an example using sleeve tubes – the brush head can be extremely small.

5.3 Brush Handle Length

How long should brush handles be?

Han Dynasty scholar Wang Chong, author of “Balanced Inquiries,” said: “Capable people need a three-inch tongue and a one-foot brush.” Meaning smart, capable people need to speak well and write well. A Han Dynasty foot was about 23 centimeters. Looking at excavated Han Dynasty brush handles, the length was indeed standardized at around 23 centimeters. By the Tang Dynasty, Chinese brushes were thicker and no longer inserted in hair, so they became shorter.

Tang Dynasty scholar Yu Shinan’s “Brush Essence Theory” says: “Brush length should not exceed six inches.”

Looking at the dozen or so Tang brushes in Japan’s Shosoin treasury, lengths are about 17-19 centimeters, equal to 5.5-6 Chinese inches today.

Current blue handles are about 18 centimeters, red handles about 21 centimeters – similar to Tang brushes, slightly shorter than Han brushes by about two centimeters. The longer the handle, the easier it bends. Look at this brush below – it’s too long and clearly bent.

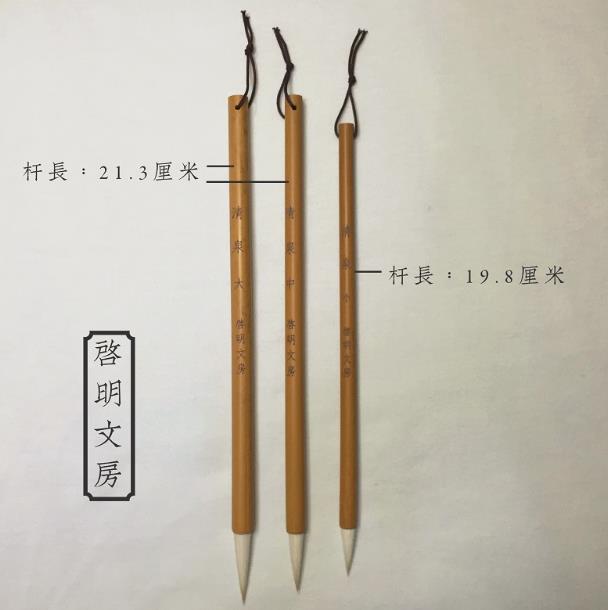

Qi Ming’s custom Qingquan Chinese brush handle is 21.3 centimeters long.

Brush tubes must be straight. When buying Chinese brushes, the inspection method is simple – roll it on a table or glass surface, and you can feel whether it’s straight. If you hear sounds when rolling – tap tap tap – then it’s not straight. (Qi Ming’s Note: Regarding this point, Qi Ming believes Chinese brushes mainly need to be round. Even if the handle is slightly bent, it’s not a big problem and won’t greatly affect writing. I think Master Huang Jian is being too strict on this point.)

6. Installing the Handle

The final step is installing the handle. This refers to joining the brush head and handle – in simple terms, how to install the brush head.

6.1 Insertion Depth

How deep should the brush head be inserted into the handle? Wei Dan said: “Insert into the tube, preferably following the hair length to make it deep.” Meaning it’s better to insert deeply. He didn’t specify exactly how deep.

As mentioned earlier, Wei Dan’s brushes required thread binding twice – once after completing the brush core, then again after adding the column and covering. This creates a brush neck, and the entire neck is inserted into the handle.

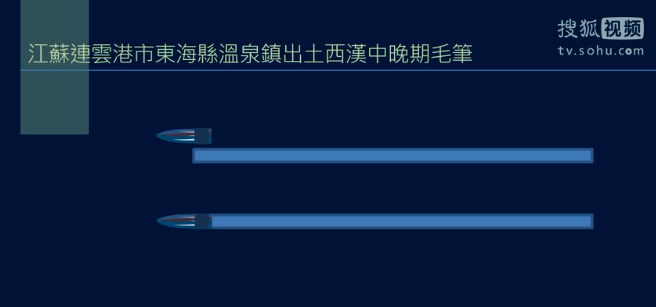

In 1993, two Western Han mid-to-late period brushes were excavated in Wenquan Town, Donghai County, Lianyungang City, Jiangsu. The brush head ends were wrapped with thread to form brush necks. One brush head was 2.3 centimeters long with 0.9 centimeters inserted into the handle; another was 3.2 centimeters long with 1.1 centimeters inserted. This means the inserted portion was one-third of the brush head length.

In 1995, a Chinese brush was excavated from a Han tomb in Haizhou Wangdun, Lianyungang City. The bristles were 4.1 centimeters long with 2 centimeters inserted into the handle – nearly half, far exceeding modern standards.

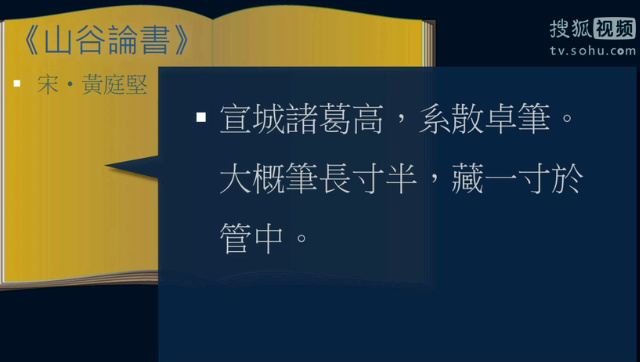

For Song Dynasty scatter-tip brushes, Huang Tingjian has specific records. He said: “Zhuge Gao of Xuancheng makes scatter-tip brushes. Generally brush length is 1.5 inches, with 1 inch hidden in the handle.”

This means two-thirds of a brush head should be bound into a neck and inserted into the handle. Deep insertion makes the brush head and handle integrate as one unit, comfortable to use. It also prevents hair loss and keeps the brush head from falling off.

This is a Chinese brush I had custom made over ten years ago. My requirement was simple – insert at least one-third of the brush head, not just a tiny bit. Later this was achieved. This brush is very obedient and basically doesn’t lose hair.

6.2 Naming

Once a Chinese brush with fixed specifications is made, it gets a nice name, like traditional Chinese medicines – Six-Flavor Rehmannia Pills, Black Chicken White Phoenix Pills, etc. Chinese dishes also have names like Kung Pao Chicken, Mapo Tofu, etc. Chinese brush names are also very literary. If you find a Chinese brush that suits you, remember the name – it’ll be easier to buy again next time.

On the brush handle are some markings. At the top of the Chinese brush is a label – this is the brand, then the brush name – meaning you give it a name yourself. Here I’ll randomly think of “Sweeping Away Thousands of Armies.” Some ordinary Chinese brushes don’t engrave names but have descriptions.

For example, common “Aged Sheep Hair Large Regular Script” means the sheep bristles used are naturally degreased over years. Or “True Winter Northern Wolf Hair” – as mentioned before, this uses winter hair from northern weasels. Or “No. 2 Capital Lift” – lift brushes are larger ferrule brushes, with numbers 1, 2, 3 indicating size. Below the brush name, the manufacturer’s name is often engraved, like “China Brush Factory” here as an example. Manufacturer names are usually in small characters.

6.3 Gluing the Head for Shape

Finally, shape the brush head, like someone getting a beautiful hairstyle and using hairspray to fix it. For Chinese brushes, seaweed is soaked in water and boiled into a gel-like substance, then applied to the brush head. This method existed in Wei Dan’s time.

Wei Dan’s “Brush Methods” says: “Bind it with a tube, fix with lacquer liquid, moisten with seaweed.” When the seaweed glue dries, it fixes the brush shape and prevents bristles from becoming fluffy and spreading. You wash off this seaweed when you start using the brush. How exactly to do this? I’ll demonstrate next time. Wei Dan’s method is still used today. However, this means when you buy a brush, you can’t see what kind of hair is inside. If you want to test its softness and hardness, the shop owner probably won’t agree.

Key Points of This Section

- Basic understanding of the Chinese brush manufacturing process

- Important considerations for material selection, mixing, shaping, and handle installation

Discussion Questions

- What are the advantages of Wei Dan brushes’ small cores versus scatter-tip brushes’ large cores?

- If you already have Chinese brushes, do they lose hair? What methods can prevent or improve this?

Note: This article is notes compiled by Qi Ming based on “Huang Jian’s Basic Calligraphy Tutorial” Episode 9 “Understanding Chinese Brushes 2.” Qi Ming will continue organizing other notes – everyone is welcome to follow along.

Comments and discussions about viewpoints in this article are welcome.