“I’m a beginner at copying Chinese calligraphy. How should I practice?” This is a question many Chinese calligraphy enthusiasts frequently ask me on WeChat. Today, Qi Ming is sharing my own experience with copying Chinese calligraphy to help beginners master this traditional art form.

Essential Preparation Before Copying Chinese Calligraphy

Before you officially start copying Chinese calligraphy, you need to choose a suitable Chinese calligraphy copybook. For guidance on how to select a copybook, please refer to Qi Ming’s previous article “How Beginners Should Choose Chinese Calligraphy Copybooks.” Once you’ve selected your copybook, we can begin the process of copying Chinese calligraphy.

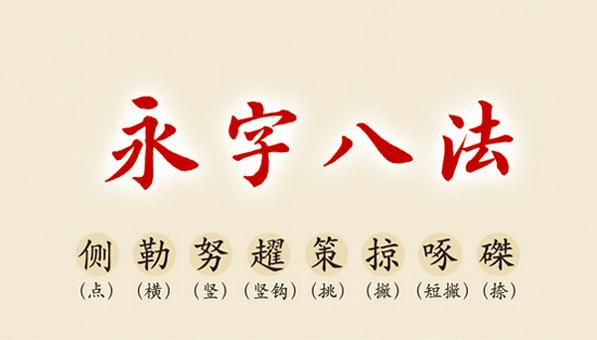

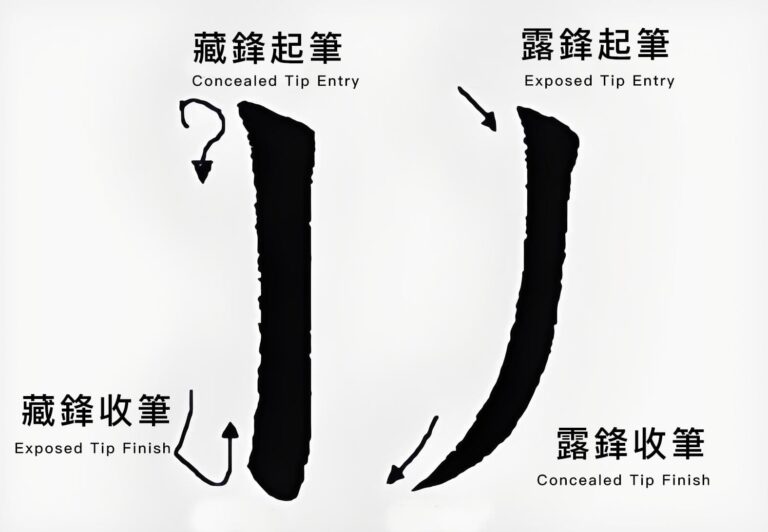

There’s one more important thing to do before copying Chinese calligraphy: master the basic strokes. When my Chinese calligraphy teacher taught me to write, he started with basic strokes. For example, with a horizontal stroke, my teacher would show me how to begin the stroke, move the brush, and end the stroke.

This is just like learning to drive a car – you need to learn how to start the car, drive it, and stop it. If you can’t write a horizontal stroke well, start with the motion of beginning that stroke. Once you’ve mastered the beginning, practice the middle movement. After you’ve practiced the middle part well, then practice the ending. Follow this same process for every stroke. This ensures your basic strokes meet the standard before you begin copying Chinese calligraphy.

After practicing the strokes well, find several characters that contain those strokes and integrate the strokes into complete characters. For example, for the horizontal stroke, you can practice characters like “三” (three), “大” (big), and “書” (book) that contain horizontal strokes.

Because each Chinese calligraphy style writes strokes differently, Qi Ming won’t go into detailed explanations here. Let’s focus on the key issue of how to write character structures accurately when copying Chinese calligraphy.

Reading Chinese Calligraphy: The Foundation of Copying Chinese Calligraphy

When you begin copying Chinese calligraphy, you need to pay attention to reading the calligraphy first. Reading Chinese calligraphy doesn’t just mean reading the text that ancient masters left behind. More importantly, it means observing how the characters in the copybook are written – this is a crucial skill for successful copying Chinese calligraphy.

For example, look at the layout and the overall feeling it gives you. Most importantly, examine how the character structure works – how does it begin? What is the relationship between each stroke and the previous strokes? What are the relationships between left and right, top and bottom, inside and outside? Understanding these elements is essential when copying Chinese calligraphy.

(I recommend everyone read Qi Ming’s previous article “How to Read Chinese Calligraphy? What Exactly Should You Read? See Mr. Wu Ruxian’s Ten Observations on Reading Calligraphy”)

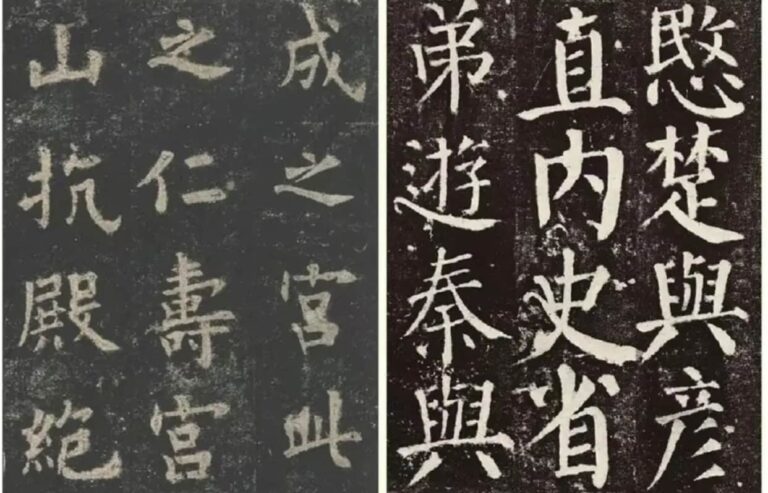

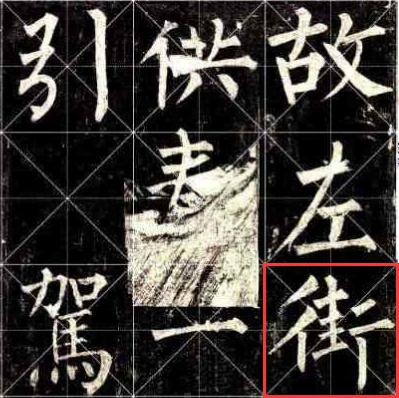

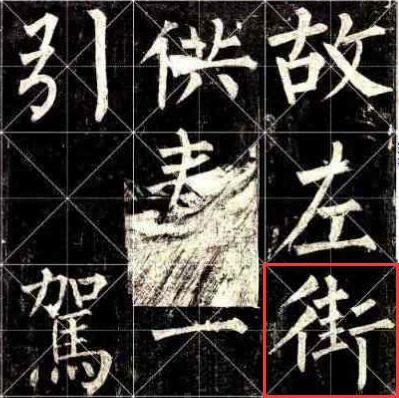

Here, Qi Ming will use the character “街” (street) that I previously copied from Liu Gongquan’s work to explain the structural aspects of copying Chinese calligraphy.

In the image below, the character “街” marked in red by Qi Ming comes from Liu Gongquan‘s classic copybook “Xuanmi Pagoda.” Let’s first observe this character “街” before copying Chinese calligraphy in this style.

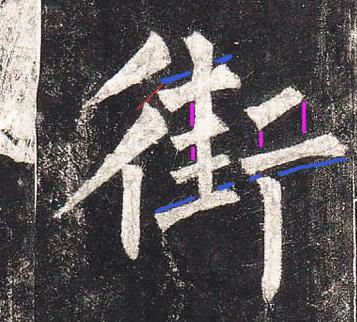

First, you’ll see the double-person radical on the left. After writing the first downward stroke, Liu Gongquan begins the second downward stroke at a position in the middle-lower area, slightly to the right of the first stroke.

When you’re copying Chinese calligraphy, if you write the second stroke too far to the right, or even directly beyond where the first stroke begins, then obviously you’ve violated the structure of Liu style. Even if you’re just writing with a regular pen, if you let the lower stroke extend too far out, it will look bad. Don’t believe me? Try it right now with a pen.

Good. Then there’s a short vertical stroke, followed by the middle character “圭.” I wonder if everyone noticed that the first horizontal stroke is written in the middle-lower position between the two short downward strokes.

Compared to today’s Song-style character “圭” (one short horizontal, one long horizontal – actually two “土” characters stacked), Liu Gongquan seems to have intentionally made the first horizontal stroke longer than the second. This is actually for the layout that follows – to prevent the top part of the “亍” character from looking too empty. These subtle details matter greatly when copying Chinese calligraphy.

Let’s look at the middle vertical stroke. Liu Gongquan wrote this vertical stroke at a position in the middle-right of the first horizontal stroke. So you can see that the line segments marked in blue by Qi Ming in the image are some long and some short. The ones on the left are longer, and the ones on the right are shorter.

So if you violate Liu Gongquan’s arrangement of long on the left and short on the right when copying Chinese calligraphy, your Liu style will be distorted. This is actually talking about the comparison of horizontal spatial relationships.

Finally, let’s look at the comparison of vertical spatial distances. Look at the character “亍.” In the Song-style font typed on a computer, the two horizontal strokes of “亍” are parallel. However, Liu Gongquan wrote these two short horizontal strokes tilting slightly upward to the right.

If you write them parallel when copying Chinese calligraphy, you’ve written the shadow of Song style, not Liu style. This is what we usually call the spatial relationship between strokes in a character. This is also important content we need to read when learning the art of copying Chinese calligraphy.

The Ancient Wisdom of Copying Chinese Calligraphy

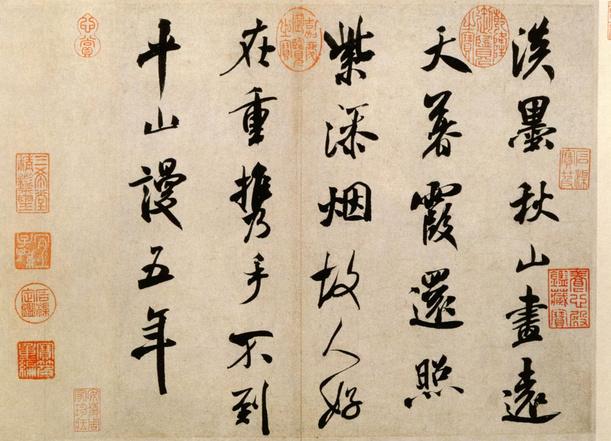

Here, Qi Ming is pasting the explanation of reading Chinese calligraphy from Baidu Encyclopedia: “Reading calligraphy is an important method for learning and copying Chinese calligraphy. The so-called ‘reading’ doesn’t mean reading aloud, but rather ‘observing.’

That is, during breaks from copying Chinese calligraphy or before you start, carefully observe and study the dots, strokes, brush usage, structure, and spirit of the characters in the copybook. Observe them with your eyes, memorize them in your heart, then practice copying them. Song Dynasty calligrapher Huang Tingjian said: ‘Ancient people learning calligraphy didn’t rely entirely on copying. They hung ancient people’s calligraphy on the wall, observed it until they understood it deeply, then when they put brush to paper, it followed their intention.'”

Huang Tingjian’s words translated into modern language mean: “Ancient people learning to write didn’t all rely on copying. They often hung ancient people’s calligraphy works on the wall and observed them with complete concentration. Only after seeing clearly would they put brush to paper.”

This shows the importance of reading Chinese calligraphy before copying Chinese calligraphy. My Chinese calligraphy teacher, Teacher Li Zhao, also has a very classic saying. He said, “Only when your eyes have observed it can your hand write it out.” This actually means the same thing as what Huang Tingjian said – before you start copying Chinese calligraphy, please first carefully observe the writing method on the copybook. If you haven’t observed it, it’s very difficult to write characters like that.

My Personal Experience Copying Chinese Calligraphy

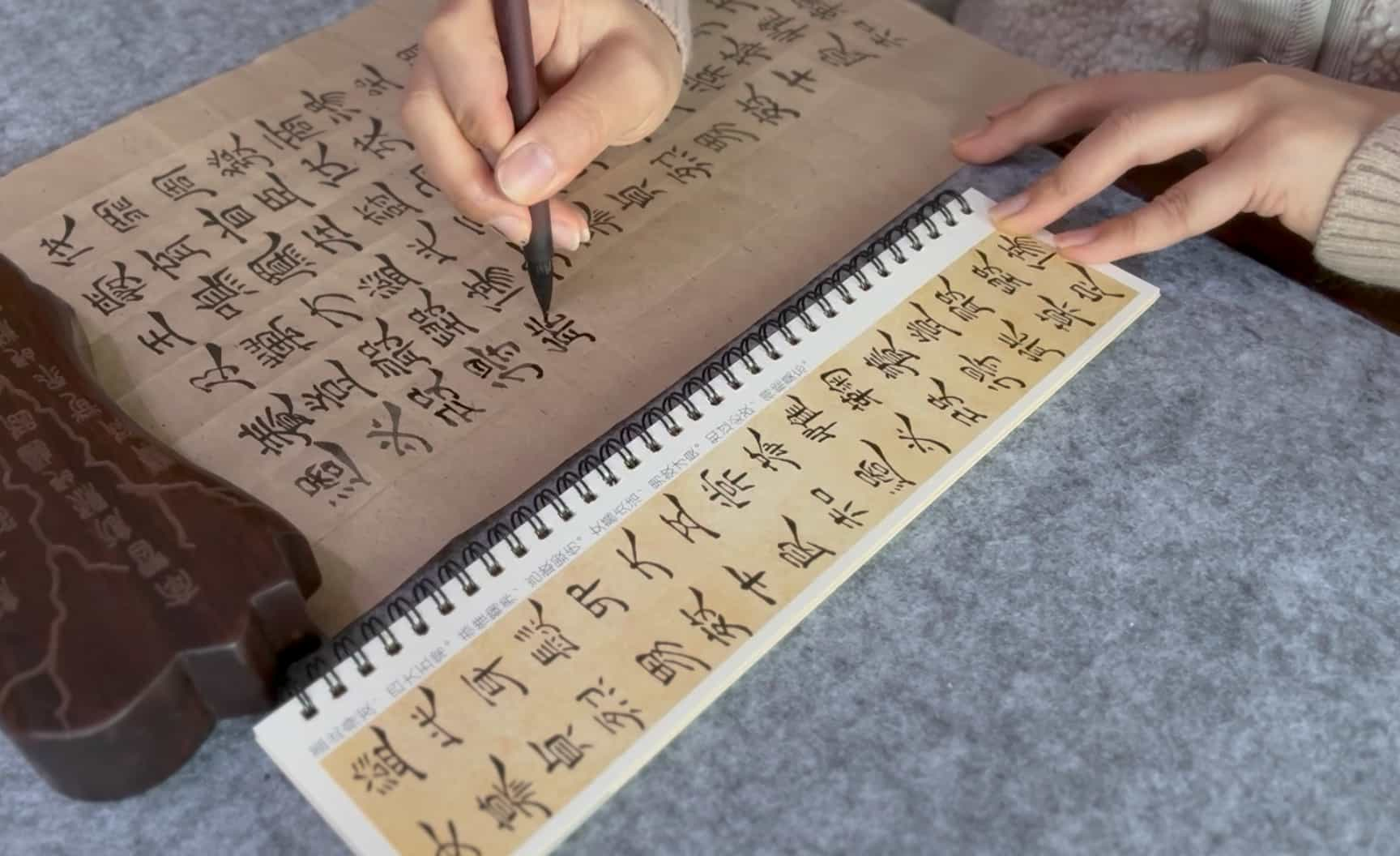

In the second image below, marked in red is the character “街” that Qi Ming wrote. This is what Qi Ming learned when copying Chinese calligraphy in the Liu style during college. At that time, I had no idea what reading Chinese calligraphy was or how to read it. I completely relied on grid paper to find the relationship between each stroke when copying Chinese calligraphy.

That is, I looked at what position on the grid the original copybook started the stroke, where it ended, and how much of the grid the left and right sides occupied. This is also why I mentioned in my previous article “Best Paper Types for Chinese Calligraphy Beginners – Complete Guide” that everyone should buy several stacks of both plain Maobian paper and Maobian paper with grids for copying Chinese calligraphy practice.

It’s worth noting that if the original copybook has grids printed on it, of course this method works well for copying Chinese calligraphy. If not, it tests your skill at reading Chinese calligraphy. Actually, I recommend that everyone carefully read the calligraphy and then write on paper without grids when copying Chinese calligraphy. Of course, in the early stages, if you really can’t grasp it, then Maobian paper with grids is better for your copying Chinese calligraphy practice.

Looking back now at the Chinese brush calligraphy I copied at that time, there are many inadequate places. If you compare it with Liu Gongquan’s original copybook that I’ve posted, combined with the method of reading and copying Chinese calligraphy I mentioned above, you’ll know exactly where the differences are.

Further Resources for Copying Chinese Calligraphy

Regarding copying Chinese calligraphy, Qi Ming recommends two more articles for everyone. I think they’re very well-written and will help you understand why copying Chinese calligraphy is so important. One is “Why Must We Copy Calligraphy When Learning Chinese Calligraphy? (Chen Zhongkang on the Significance of Copying Calligraphy),” and the other is “Why Must We Start with Copying When Learning Chinese Calligraphy? (Mr. Qi Gong on Copying Calligraphy).” After reading them, everyone will have a deeper understanding of copying Chinese calligraphy.

Conclusion: Mastering the Art of Copying Chinese Calligraphy

Learning the art of copying Chinese calligraphy is a journey that requires patience, careful observation, and consistent practice. From mastering basic strokes to understanding the spatial relationships between each element of a character, every step in copying Chinese calligraphy brings you closer to this art form that has been perfected over thousands of years.

Remember, reading Chinese calligraphy is just as important as copying Chinese calligraphy itself. Take time to observe the original masterworks, understand the structure and flow of each character, and only then put brush to paper. Whether you use grid paper as a guide in the beginning or challenge yourself with blank paper, the key to successful copying Chinese calligraphy is to keep practicing and refining your technique.

At Qi Ming Wen Fang, we encourage all beginners to embrace the beautiful traditional practice of copying Chinese calligraphy with dedication and joy. Through consistent practice of copying Chinese calligraphy, you’ll not only improve your writing skills but also connect with centuries of artistic tradition.

If you want to learn more about Chinese brushes, you can read the following articles

Top 10 Chinese Calligraphy Brushes: The Ultimate Guide to Selection and Care

Best Calligraphy Brushes for Beginners: Complete Guide to Choosing Your First Writing Brush