Whether in calligraphy textbooks or from Chinese calligraphy teachers, when students first begin learning Chinese brush writing, they often encounter a fundamental concept called the “Eight Principles of Yong” (永字八法).

But what exactly are the Eight Principles of Yong? Why do calligraphy beginners need to practice the Eight Principles of Yong first? And is mastering the Eight Principles of Yong really enough to become proficient in calligraphy?

Today, Qi Ming has compiled this comprehensive article focusing on the Eight Principles of Yong and the perspectives of two respected masters: Mr. Qi Gong and Mr. Tian Yuncang on this foundational technique.

Historical Perspectives on the Eight Principles of Yong

Let’s first look at Mr. Qi Gong’s views on the Eight Principles of Yong from the 1960s during the “Lanting Debate” initiated by Guo Moruo:

The Eight Principles of Yong is an ancient teaching method that uses the character “Yong” (永) as an example to systematically explain the essential brush techniques for eight basic strokes in regular script calligraphy.

Regarding its origins, historical accounts vary. The Eight Principles of Yong likely emerged during the Sui and Tang dynasties when regular script calligraphy flourished. Calligraphy masters created this teaching method to guide beginners by using the first character “Yong” from Wang Xizhi’s “Lanting Xu” (Preface to the Orchid Pavilion), which is renowned as “the greatest calligraphy work under heaven.” They developed the Eight Principles of Yong approach to simplify complex techniques and “open the eyes to understanding characters.”

Understanding the Eight Strokes in the Eight Principles of Yong

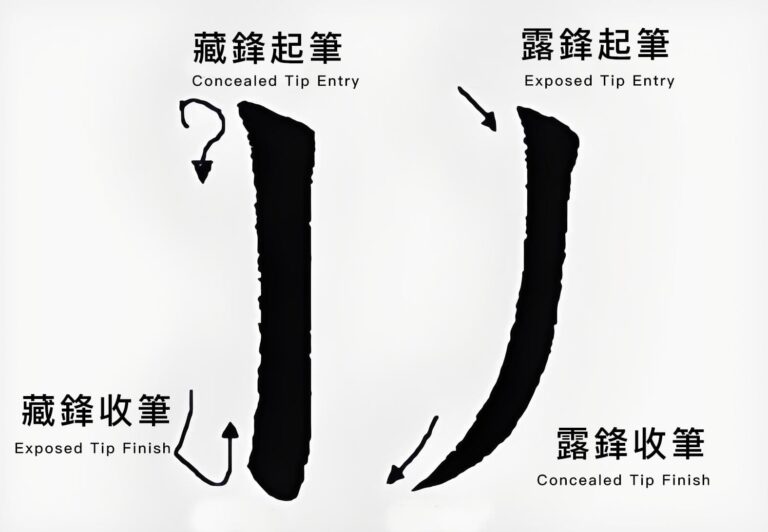

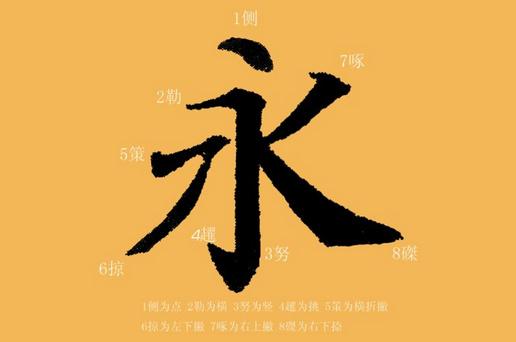

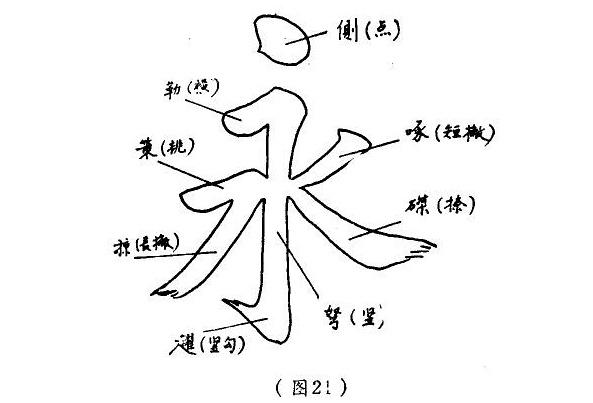

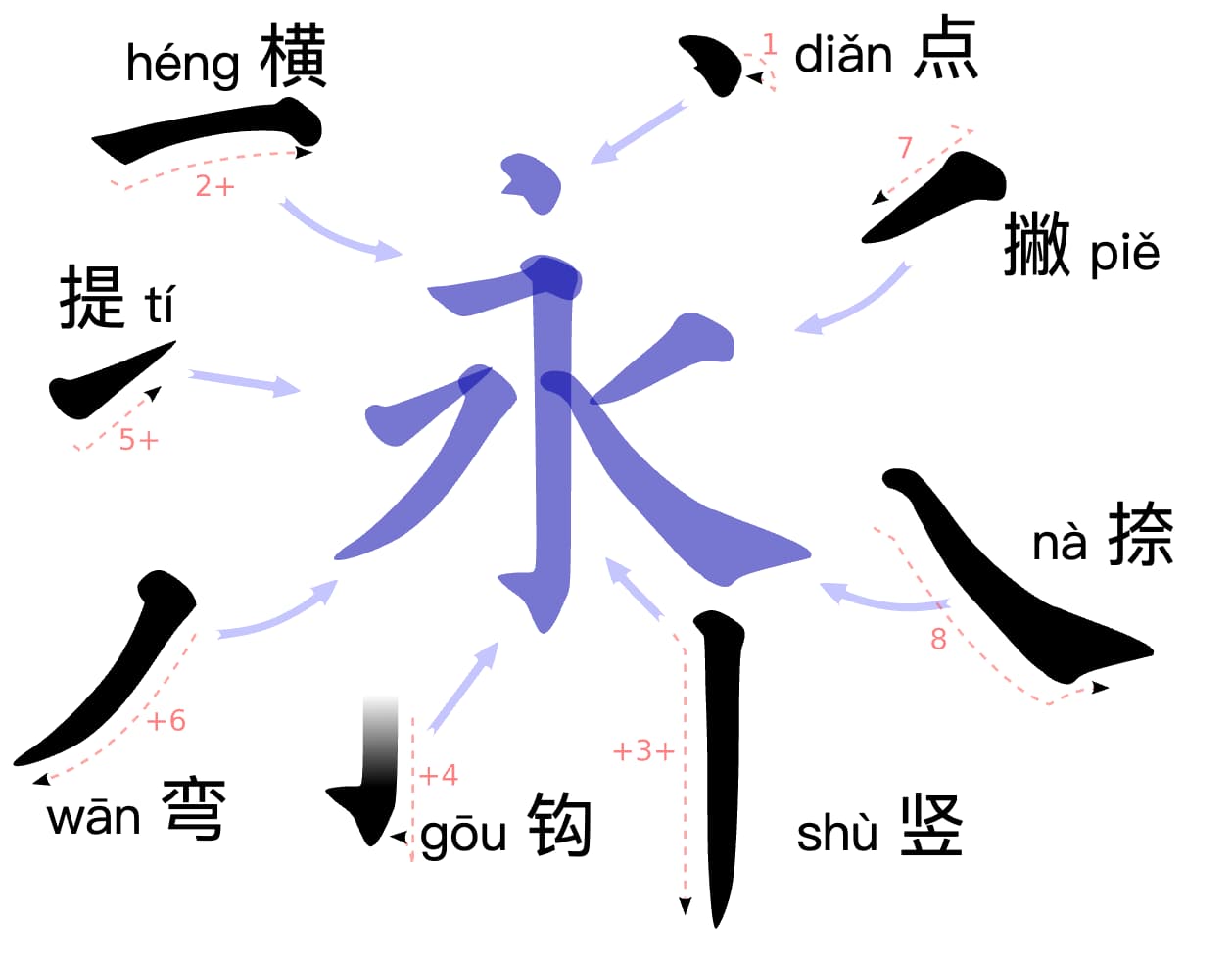

In the Eight Principles of Yong, the strokes are named: dot is called “ce” (侧), horizontal stroke is “le” (勒), vertical stroke is “nu” (弩), vertical hook is “ti” (趯), upward flick is “ce” (策), long left-falling stroke is “lüe” (掠), short left-falling stroke is “zhuo” (啄), and right-falling stroke is “zhe” (磔) (see image below).

The Eight Principles of Yong

Although these stroke names in the Eight Principles of Yong seem unusual, each contains metaphorical meaning that indicates how the stroke should be written to achieve proper strength and spirit. Let me explain each principle briefly:

① Ce (Dot) – First of the Eight Principles of Yong

“Ce” means tilted or slanted. The dot should lean at an angle, like a massive boulder standing at a slant—powerful and commanding. If the dot lies flat or stands completely upright, it becomes dull and lifeless. In this “Yong” character, the dot finishes with an exposed tip to connect visually with the horizontal stroke below, creating continuous rhythm.

② Le (Horizontal Stroke)

The horizontal stroke slants slightly upward, like a rider pulling tight on the horse’s reins, with force directed inward straight into the “nu” (vertical stroke). If written lying flat or slanting downward, it appears weak and powerless.

③ Nu (Vertical Stroke)

“Nu” means forceful. The vertical stroke maintains an inwardly straight yet outwardly curved position, like a drawn bow standing upright—although curved in appearance, it contains infinite strength. Therefore, the vertical stroke shouldn’t be too straight; overly straight strokes resemble dead wood planted in the ground—upright but lifeless.

④ Ti (Hook)

“Ti” shares the same meaning as “leap.” When making the hook, first press down the brush to build momentum, then quickly lift the brush and release the tip in a flowing motion. It’s like a person preparing to jump—they must first crouch down to gather strength, then suddenly leap upward. The tip doesn’t exit horizontally because it needs to connect visually with the “ce” (upward flick) stroke.

⑤ Ce (Upward Flick)

“Ce” originally means whip, but here refers to the concept of coordination. The upward flick is usually used on the left side of characters, angling upward to the right to coordinate with related strokes on the right side, creating a sense of balance and harmony. In the “Yong” character, this stroke extends slightly horizontally to coordinate with the “zhuo” (short left-falling stroke) on the right. Although these two strokes are staggered and asymmetrical, their energy flows in harmony.

⑥ Lüe (Long Left-Falling Stroke)

“Lüe” means to brush or sweep. Writing this stroke should feel like brushing one’s hand across an object’s surface. Although the brush movement gradually accelerates and the ending is light and swift (compared to the right-falling stroke), creating an elegant and clean appearance, the force must reach all the way to the tip. Otherwise, it will appear unsteady.

⑦ Zhuo (Short Left-Falling Stroke)

“Zhuo” means to peck. Writing this short left-falling stroke should resemble a bird pecking at food with its beak—quick movement with a sharp brush tip, different from the long left-falling stroke.

⑧ Zhe (Right-Falling Stroke) – Final Principle

This naming is the most difficult to understand, but we believe it contains two layers of meaning.

First, regarding the role of this stroke in character structure: “Zhe” originally means to dismember sacrificial animals, carrying the sense of separating and spreading out. The right-falling stroke in regular script comes from the wave-like strokes in clerical script. These spreading strokes in clerical script were designed to break apart the curved and confined form of small seal script (the diagonal spreading strokes in clerical script were all downward curves in small seal script), making the character’s posture open outward. That’s why clerical script is also called “fen shu” (分書, separated script). The right-falling stroke in regular script serves the same purpose.

In regular script, the left-falling and right-falling strokes gather strength inward while spreading outward in form, making the character’s posture stretch out and appear lively. If you replace the long right-falling stroke in “Yong” with a short side dot, the force remains gathered inward, but the dynamic energy immediately disappears. For this reason, the right-falling stroke must always be written open and stretched to display spirit.

Second, this stroke must be written with strength, sharpness, and momentum. Since “zhe” originally meant dismembering sacrificial animals, and dismembering requires a knife to split, the “zhe” (right-falling stroke) takes on the momentum of knife-splitting. In southern regions, the right-falling stroke is commonly called “knife left-falling stroke,” probably originating from this concept.

Analyzing the Eight Principles of Yong

Previous scholars have provided many explanations of the Eight Principles of Yong. However, some are too simple and unclear in meaning, others are too abstract and impractical, and many contain contradictions. Some valuable interpretations exist but are often fragmented and lack systematic organization.

Here we use a practical approach, exploring the creator’s original intent while drawing from previous insights and combining our own experience, striving to explain the Eight Principles of Yong thoroughly and practically for modern use.

The Eight Principles of Yong use one character to summarize the basic writing methods for eight fundamental strokes in regular script (not exactly the same as the eight basic strokes we mentioned earlier; the Eight Principles don’t include the turning stroke). Therefore, people have always believed that the Eight Principles of Yong specifically teach stroke techniques—”The Eight Principles of Yong are just about strokes” (Lu Chao’s words).

But this isn’t entirely accurate. The strokes in the Eight Principles of Yong aren’t isolated; they represent eight specific strokes within one character. When we explore why each stroke should be placed and written in this particular way, we’re actually touching upon the principles of character structure.

Therefore, the author’s intention with the Eight Principles of Yong was to explain basic stroke writing and their combination through analyzing one character (essentially how to make and assemble parts—what shape the parts take must serve the needs of assembly), enabling beginners to apply these principles broadly and grasp the general requirements for brush techniques and structural composition in regular script (and actually running script too).

The Value and Limitations of the Eight Principles of Yong

For this reason, after the Eight Principles of Yong emerged, they received praise from many calligraphers throughout history. Some even praised the Eight Principles of Yong excessively. For example, one claim states that Wang Xizhi “practiced calligraphy for many years, focusing on the character ‘Yong’ for fifteen years, because it contains the eight principles and can lead to understanding all characters” (from “Hanlin Jin Jing” quoting Li Yangbing).

Today we should analyze both the Eight Principles of Yong and previous evaluations of them carefully, without blind faith. If you truly believe the Eight Principles of Yong “can lead to understanding all characters” and spend fifteen years focusing only on “Yong” without writing other characters, the result would likely be that you wouldn’t become a “calligraphy sage,” or even a “calligraphy servant.”

In summary, the Eight Principles of Yong can help us understand that there’s a balanced relationship between stroke techniques and structural composition in regular script, providing helpful inspiration for practicing brush techniques and character structure. However, the Eight Principles of Yong absolutely don’t encompass all the content and techniques of calligraphy. We shouldn’t reject the Eight Principles of Yong, but we also shouldn’t treat them as the ultimate “secret method” for learning calligraphy.

Tian Yuncang’s Perspective on the Eight Principles of Yong

Regarding the Eight Principles of Yong, Professor Tian Yuncang mentioned them in the first episode of his program “Tian Yuncang’s Daily Topic, Daily Character.” Here, Qi Ming presents Professor Tian’s views on the Eight Principles of Yong and his differing opinion from Mr. Qi Gong regarding their origins.

First, let’s look at the two theories Professor Tian proposed about the origins of the Eight Principles of Yong:

Theory One: The Lanting Connection

One theory suggests that in Chinese history, Wang Xizhi from the Eastern Jin Dynasty is considered the highest representative of calligraphy achievement. His masterpiece, known as “the greatest running script under heaven,” is the “Lanting Xu” (Preface to the Orchid Pavilion). The first character in “Lanting Xu” is “Yong”—from the phrase “In the ninth year of Yonghe, the year of Guichou.”

Therefore, one theory holds that since everyone should learn Eastern Jin calligraphy, and the Eastern Jin period should primarily be represented by Wang Xizhi, and Wang Xizhi’s work is best represented by “Lanting Xu,” and the first character of “Lanting Xu” is “Yong,” everyone should first learn the character “Yong.” This is one theory about the Eight Principles of Yong.

Theory Two: Comprehensive Stroke Learning

The second theory holds that the character “Yong” doesn’t have many strokes, but contains numerous brush techniques. Therefore, learning “Yong” through the Eight Principles of Yong allows one to apply knowledge broadly—it has this effectiveness. For this reason, some people propose learning this “Yong” character first.

The True Origins of the Eight Principles of Yong Revealed

Regarding the real origins of the Eight Principles of Yong and discussions about them, Professor Tian Yuncang’s view is as follows:

Actually, the establishment of the Eight Principles of Yong wasn’t entirely based on Wang Xizhi. That the first character of Wang Xizhi’s “Lanting Xu” is “Yong” and the “Eight Principles of Yong” is purely coincidental. They don’t have this relationship. We have evidence to present to everyone.

Why do we say that the Eight Principles of Yong didn’t originate from Wang Xizhi’s “Lanting Xu”? Let’s look at this: during the Tang Dynasty, there was a calligraphy theorist named Zhang Huaiguan who wrote a book called “Yutang Jin Jing,” which contains a section on “Brush Usage Methods.” It clearly explains the earliest source of the Eight Principles of Yong.

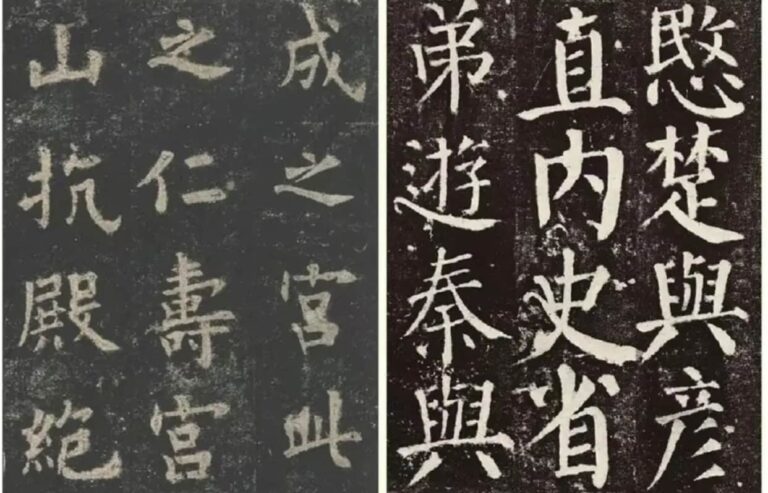

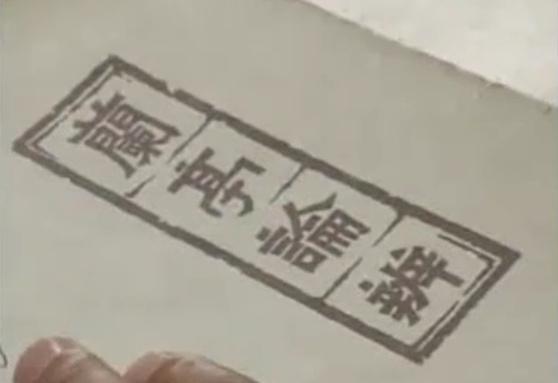

To make this clear for everyone, I’ll copy this passage with my brush now for you to see:

“The Eight Principles originated at the beginning of clerical script, from Cui Ziyu of the Later Han, passed down through Zhong and Wang…”

“The eight forms used encompass ten thousand characters…”

Look at this passage from Zhang Huaiguan in “Yutang Jin Jing.” He says “The Eight Principles originated at the beginning of clerical script”—everyone notice, this “clerical” doesn’t refer to clerical script, but refers to regular script. Because during the Tang Dynasty, regular script was called clerical script; during the Eastern Jin period, Wang Xizhi and others also called it this. What we now call clerical script was then called “ba fen.” So until the Tang Dynasty, regular script was still called “clerical script.”

He says “The Eight Principles originated at the beginning of clerical script,” meaning at the beginning of regular script. So when did this time period start? It began with Cui Ziyu of the Later Han. “Cui Ziyu of the Later Han” refers to Cui Ziyu from the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty. Who are “Zhong and Wang” in “through Zhong and Wang”? They are Zhong You and Wang Xizhi. Before Wang Xizhi, there were Cui Ziyu and Zhong You.

Then “below Zhong and Wang”—notice this “yi” character, the original text uses “yi” meaning “already,” but in ancient texts, “yi” (以) and “yi” (已) are interchangeable. We now use “yi” (已) instead of “yi” (以).

So back in the Han Dynasty, Cui Ziyu already had the Eight Principles of Yong, and they were “passed down” all the way to Wang Xizhi. Therefore, the Eight Principles of Yong didn’t begin with Wang Xizhi.

The “eight forms” mentioned here refers to the Eight Principles, and “encompass ten thousand characters” means that writing “Yong” well benefits ten thousand characters. That’s the meaning.

Therefore, everyone should know that Mr. Qi Gong’s claim that the Eight Principles of Yong originated from the “Yong” character in Wang Xizhi’s “In the ninth year of Yonghe” is inaccurate. This is one issue.

Why the Character “Yong” Works for the Eight Principles of Yong

Another point is that the character “Yong” in the Eight Principles of Yong doesn’t have many strokes. Look at it—actually it only has dot, horizontal, vertical, hook, upward flick, long left-falling stroke, short left-falling stroke, and right-falling stroke. According to our current stroke counting, it has a total of five strokes, and within these five strokes, it contains eight principles.

Therefore, “Yong” has no repetitive strokes. In just these few strokes, there are this many principles. Characters like this aren’t commonly found. Although the Eight Principles of Yong don’t encompass all brush techniques—we can say no single character can encompass all brush techniques, impossible—for “Yong” to include so many principles within such simple strokes is already very rare to find another character that can compare.

So, learning the Eight Principles of Yong, first, it’s not as Mr. Qi Gong said, beginning from Wang Xizhi’s “Lanting Xu.” No. The Eight Principles of Yong already existed in the Later Han. From Cui Ziyu through “Zhong and Wang,” Zhong and Wang were also during the Later Han period (Zhong You was) a military officer under Cao Cao during the Three Kingdoms. Therefore, by the time of Wang Xizhi, it was already over a hundred years later. Because Wang Xizhi wrote “Lanting Xu” in 353 CE, with over a hundred years in between. So Mr. Qi Gong’s statement is inaccurate.

————Dividing Line————

Conclusion: Mastering the Eight Principles of Yong and Beyond

Based on the above, everyone should understand why the concept of the Eight Principles of Yong is so popular in Chinese calligraphy education. Of course, you also understand that merely mastering the Eight Principles of Yong is absolutely not enough to become a skilled calligrapher.

In Qi Ming’s view, the greatest inspiration the Eight Principles of Yong gives us is this: when learning calligraphy, try to find typical model characters with representative strokes to practice. This way, you can master the writing techniques of a particular stroke in a relatively short time, thereby achieving rapid improvement.

The Eight Principles of Yong serve as an excellent foundation for beginners learning Chinese brush calligraphy, but they are just the beginning of a lifelong journey in mastering this ancient art form.

You May Also Like:

Chinese Calligraphy Ink: Ink Stick vs Liquid Ink Guide

What is Xuan Paper Made of? Complete Materials Guide

How Did Ancient Chinese Calligraphers Hold Their Brushes?

Top 10 Chinese Calligraphy Brushes: The Ultimate Guide to Selection and Care