Many people often wonder about a fundamental question: how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy? What makes a calligraphy work good? This article comes from Mochi, a highly respected public account among calligraphy professionals. I find it extremely comprehensive, so I’m sharing it here for everyone’s reference on how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy.

The full text is as follows:

Historical Standards for Evaluating Calligraphy

When learning how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy, it’s helpful to understand traditional evaluation standards. Kang Youwei, in his work “Guang Yi Shuang Ji – Sixteen Schools,” proposed ten evaluation standards, known as the “Ten Beauties”: “First is powerful strength, second is radiant atmosphere, third is leaping brushwork, fourth is bold strokes, fifth is unique grace, sixth is flying spirit, seventh is rich interest, eighth is penetrating structure, ninth is naturally formed composition, and tenth is abundant vitality.”

Guo Shaoyu, in “How to Appreciate Calligraphy,” presented six standards: “First, form – look at naturally formed structure and harmonious horizontal and vertical lines. Second, power – observe from brush strength and ink usage. Third, grace – should be dynamic. Fourth, style – not rigidly bound to stone inscriptions or model books, don’t judge model books by stone inscription standards. Fifth, knowledge – relationships beyond calligraphy itself. Sixth, atmosphere – simple and serene.”

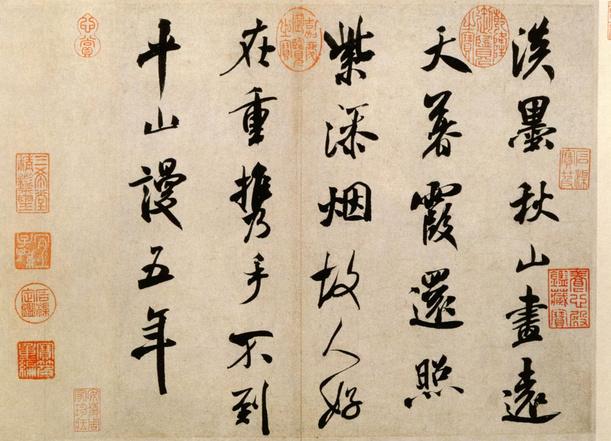

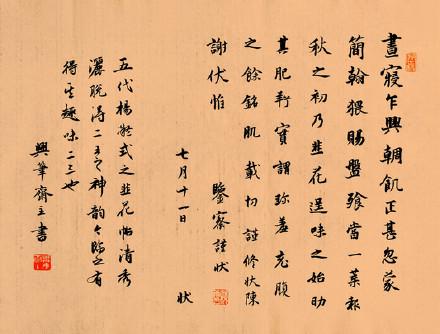

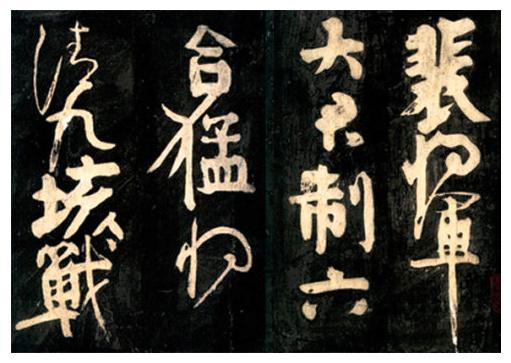

Liu Gongquan‘s “Mengzhao Tie”

These can all serve as references when you’re learning how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy. If we summarize further, it comes down to two key elements: “form” and “spirit.”

“Form” refers to the outward appearance created by special brush strokes and lines, including the strokes themselves, character structure, and overall layout of a piece.

“Spirit” refers to the inner essence within this outward form, including brush strength, momentum, expression, emotion, and other aspects.

Therefore, to properly appreciate Chinese calligraphy, we should not only look at each dot and stroke, each character, and the overall appearance, but more importantly, examine its brush strength, momentum, and spirit. If the outward form is beautiful and varied, while the inner quality is vibrant and spirited, this is what people commonly call a “perfect combination of form and spirit” – a truly excellent work.

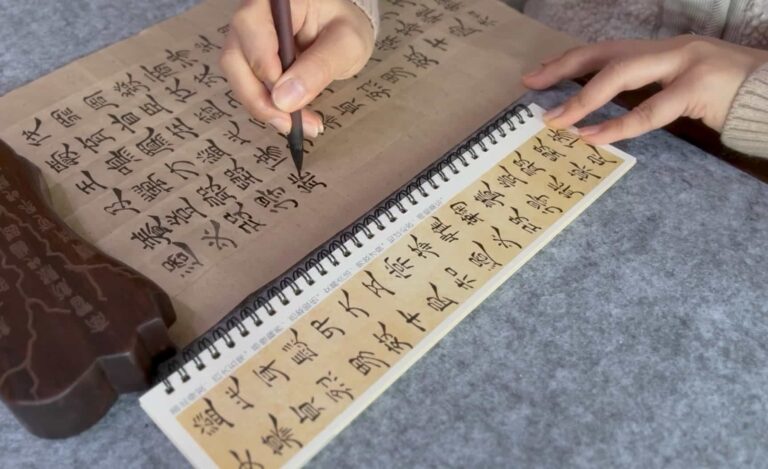

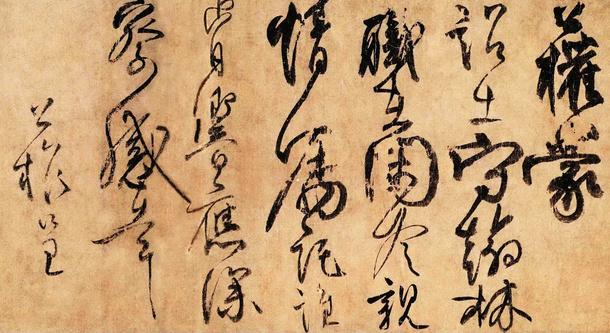

Yang Ningshi’s “Jiuhua Tie” practice work

Eight Key Aspects for How to Appreciate Chinese Calligraphy

Understanding how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy requires analyzing works from multiple perspectives. We can examine Chinese calligraphy art from the following eight aspects:

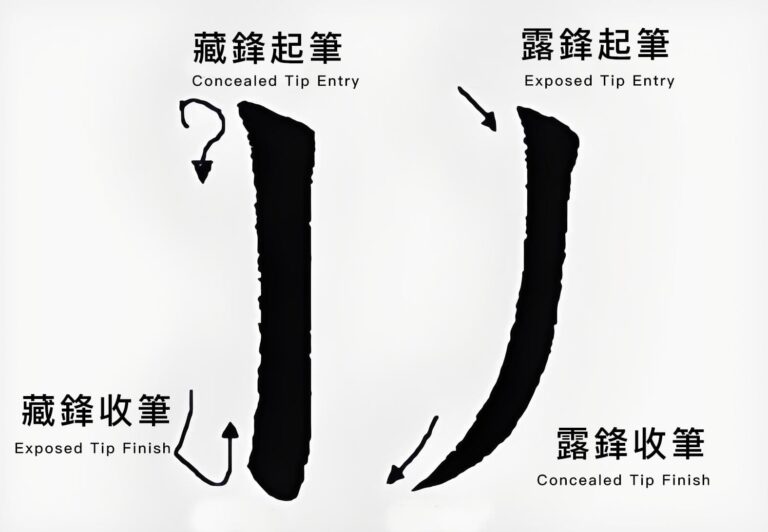

1. Variation in Stroke Length, Thickness, and Ink Tone

When you appreciate Chinese calligraphy, pay attention to how strokes vary. Chinese characters are organically composed of several line-like strokes. These strokes, especially identical strokes within a single character, should not be exactly the same in length, thickness, or ink density. They should and must vary.

For example, with the four “pie” (left-falling) strokes in the character “duo” (多), Emperor Taizong of Tang believed they should be written as follows: the first should be shortened, the second slightly less shortened, the third also shortened, and the fourth should extend with its tip.

Here, “shortened” means the stroke momentum contracts without extending, implying “short.” “Extending with tip” means the stroke momentum extends without contracting, implying “long.”

This applies not just to the “pie” strokes in “duo,” but to all other strokes as well. Otherwise, the character form appears stiff and monotonous, lacking any artistic quality.

2. Center of Gravity and Stability

An important skill in how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy is recognizing balance. Character postures can and should be diverse and varied, but we must not neglect the need to “stabilize” the character’s center of gravity.

Ouyang Xun’s characters, at first glance, seem about to topple over. But upon closer inspection, they resemble ancient towers thousands of years old. Though appearing to lean, their “center of gravity” never leaves the ground, remaining as stable as when new.

Some poorly written calligraphy appears perfectly balanced when lying flat on paper, neither leaning left nor right. But when stood upright, it often tilts this way and that, with an unstable center.

Therefore, the simplest method to judge a character’s center of gravity is to stand the paper upright and see if it “collapses.”

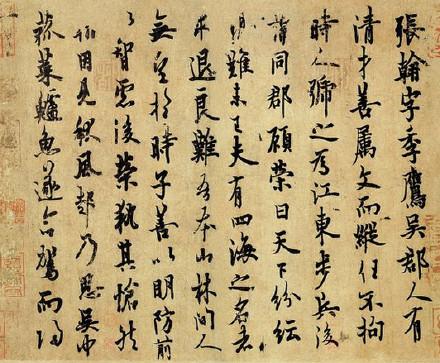

Ouyang Xun‘s “Zhanghan Tie”

3. Natural Character Momentum

Song Dynasty scholar Wang Anshi had a famous saying about calligraphy: “No need to force it to reach divine quality.”

“No need to force it” means what calligraphers and calligraphy theorists throughout history have consistently emphasized – to be “natural and appropriate.”

Wang Xizhi, when passing on calligraphy experience to his son Wang Xianzhi, said: characters should be “naturally appropriate in width and narrowness,” with “spacing between strokes well-distributed, distances evenly maintained, upper and lower parts properly placed, naturally balanced.”

Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy achieved “unique beauty” precisely because of its “naturally inherent quality.” This is the key to making calligraphy beautiful.

4. Overall Composition and Flow

When you appreciate Chinese calligraphy, examining the overall composition is essential. A good calligraphy work, like a good landscape painting, must have continuous momentum between characters and between lines. Though individual brush strokes end, the artistic flow continues.

Empty space is as important as the ink itself. When density is appropriate, it gives people infinite imagination and strong artistic appeal.

The signature and seals in a calligraphy work are also organic parts of the whole. Pay attention to whether they are used just right, adding finishing touches to the work. If they’re unnecessary additions, they can damage the artistic quality of the entire piece.

5. Technique: Following Rules While Innovating

To fully appreciate Chinese calligraphy, you need to understand the balance between tradition and innovation. Calligraphy art has extremely strong inheritance. Writers must follow certain rules and standards.

However, mere inheritance, even writing exactly like the ancients, cannot be considered true calligraphy art. At best, it’s merely copying someone else’s style without originality. There must be innovation based on inheritance.

Therefore, when evaluating and appreciating calligraphy works, we should examine whether the work properly handles the relationship between inheritance and innovation.

6. Understanding Historical Context

Learning how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy also means understanding context. Like literary works, calligraphy works are closely connected to the author’s mood while writing. The artistic style often changes with the author’s age and emotional state.

The same calligrapher can produce quite different or even completely different works during different periods and moods.

For example, Yan Zhenqing’s “Duobao Pagoda Stele,” written in his middle period during peaceful and successful times, has dignified, solid, clear, and pleasing character forms, becoming a masterpiece of regular script.

His late-period work “Jisizhi Manuscript” was written when the imperial court was in crisis and his nephew had tragically died. His grief and indignation poured out, resulting in varying stroke density, spacing, and size, with crossing-out and corrections creating a bold, free-spirited style that became a masterpiece of running script.

Therefore, we must evaluate and appreciate works within their historical context to reach correct conclusions.

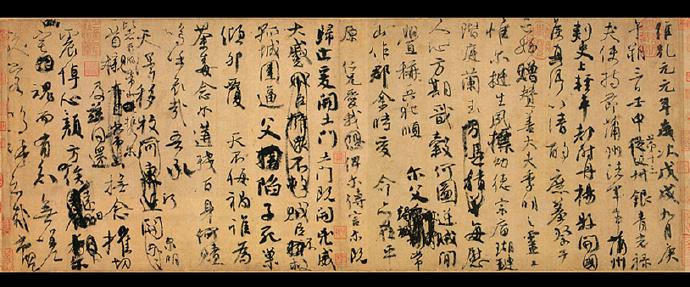

Yan Zhenqing‘s “Jisizhi Manuscript”

7. Using Artistic Imagination

A crucial aspect of how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy is developing artistic imagination. Chinese calligraphy has pictographic qualities. Character forms are structured from special linear strokes.

For such a special art form, if we only judge literally without any imagination, we cannot taste its wonderful qualities. Therefore, calligraphers throughout history have always used rich imagination to give calligraphy art reasonable metaphors.

For example, Wang Xizhi compared horizontal and vertical strokes respectively to “like a lone boat crossing the river” and “like spring bamboo shoots emerging from a cold valley.”

Emperor Wu of Liang described Xiao Ziyun’s calligraphy as “writing like steep peaks blocking view, a single pine tree, thorns bearing swords, strong men drawing bows, brave men hunting tigers, fierce hearts, sharp blades hard to resist.” He compared Xiao Sihua’s calligraphy to “dancing girl bending waist, immortal whistling at trees.”

This vividly depicts two calligraphy styles with completely different artistic qualities.

8. Mental Practice Through Visual Tracing

The final technique for how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy is mental practice. After viewing a calligraphy work’s overall beauty, you can also start from the first stroke of the first character. Let your eyes follow the brush traces, and according to the original author’s brush intention, use your eyes and mind to “re-write” the characters. This is an “internal imitation” of the calligraphy work.

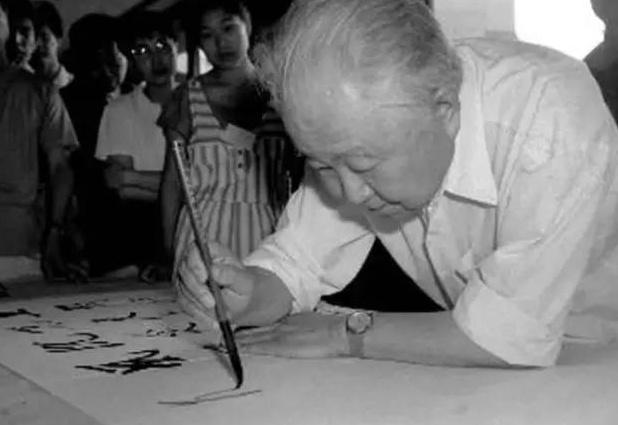

Yan Zhenqing’s “Pei Jiangjun Shi”

Through this spiritually connected “internal imitation” rewriting, you can feel the original author’s brush direction and angle, the pressure points of the brush tip and the lightness and urgency of lifting and pressing, the movement and force changes at the brush end, the connections and orientations between strokes, the mutual support and response among strokes.

You’ll appreciate the lightning speed and circling flow of cursive script, the dignified and orderly nature of regular script, the graceful ease and flexible pace of running script.

Through this, you grasp calligraphy’s vitality, interest, style, and artistic realm, effectively improving your calligraphy appreciation ability.

Conclusion

Now that you understand how to appreciate Chinese calligraphy through these eight key aspects, you can begin to develop a deeper understanding of this ancient art form. Whether you’re a beginner or looking to deepen your knowledge, these principles will guide you in recognizing the beauty, skill, and artistic expression in Chinese calligraphy works. Remember, the more you practice appreciating Chinese calligraphy, the more you’ll discover its profound cultural significance and artistic depth.

You May Also Like:

Top 10 Chinese Calligraphy Brushes: The Ultimate Guide to Selection and Care

Authentic Yi De Ge Ink Guide: Review and Verification Methods

Best Stone Materials for Chinese Seal Carving: A Complete Guide