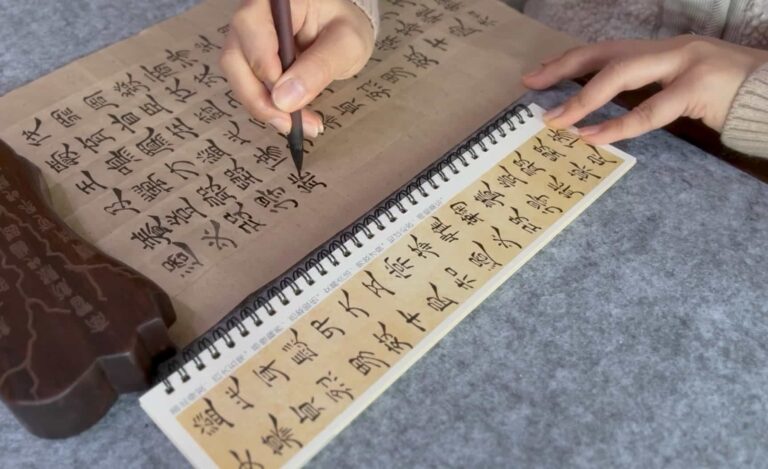

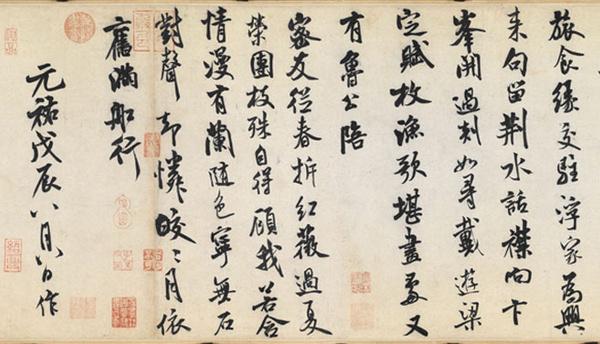

Learning Chinese calligraphy requires more than just practice—it requires learning how to “read” calligraphy works. But what exactly should we look for when reading calligraphy? How do we train our eyes to see what matters?

Previously, Qi Ming touched on this topic in the article “Copying Chinese Calligraphy: A Complete Guide for Beginners.” However, due to limited experience at the time, that article only briefly discussed structural aspects without going into depth about the important details of reading and copying calligraphy.

Today’s article is written by Mr. Wu Ruxian, and I’m sharing it here with everyone.

Develop Your Eye Through Careful Observation

Careful observation is essential for every character you practice—this is what we call “reading calligraphy.” Mr. Wu Ruxian, a distinguished calligrapher and calligraphy educator, has summarized what he calls the “Ten Observations” for reading calligraphy. These observations are extremely valuable for training your eye and truly understanding both calligraphy works and the principles behind this art form.

The Ten Observations for Reading Chinese Calligraphy

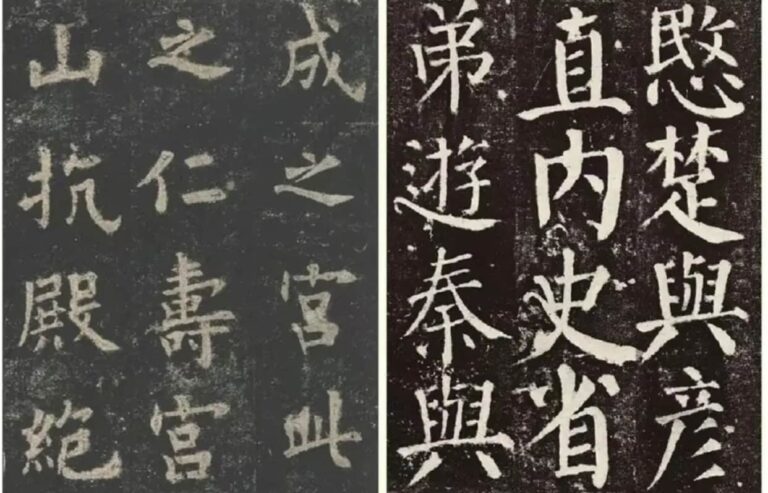

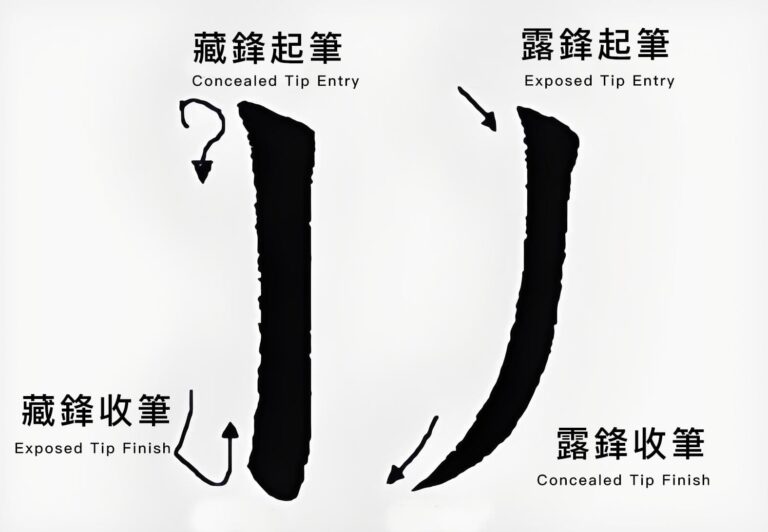

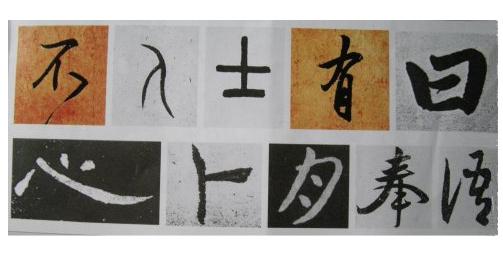

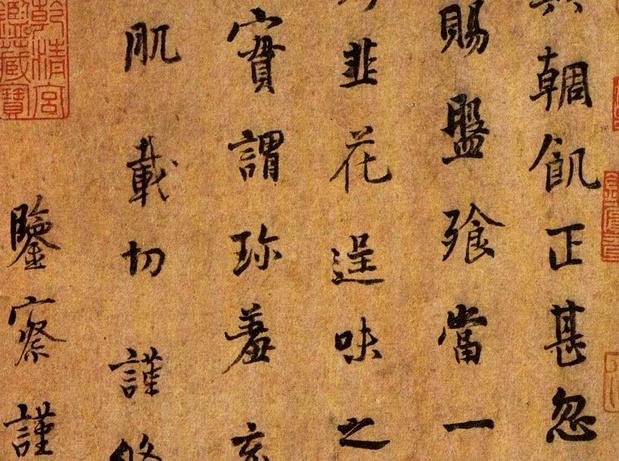

First, observe the beginning of each stroke. Look carefully to see whether the brush tip is exposed or concealed at the start. (For more details about concealed and exposed brush tips, please refer to the article “What is Concealed Tip? What is Exposed Tip? Illustrated Guide to Concealed and Exposed Brush Techniques.”)

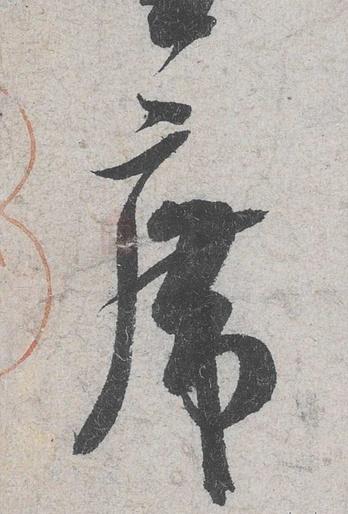

Second, observe the movement of the brush. Pay attention to the pauses, lifts, and variations in pressure as the brush moves.

Third, observe where the brush stops. See clearly how each stroke ends.

Fourth, observe the turns and corners. Determine whether they are executed with square or rounded brush movements.

Fifth, observe where strokes connect. Notice whether strokes are connected or separated.

Sixth, observe the relationship between different parts of each character. Look at the balance between dense and sparse areas, and how elements are distributed.

Seventh, observe each character as a whole. Examine the angles, proportions, and overall size relationships.

Eighth, observe the spirit of the ink and brush. Try to grasp the energy and momentum of each character.

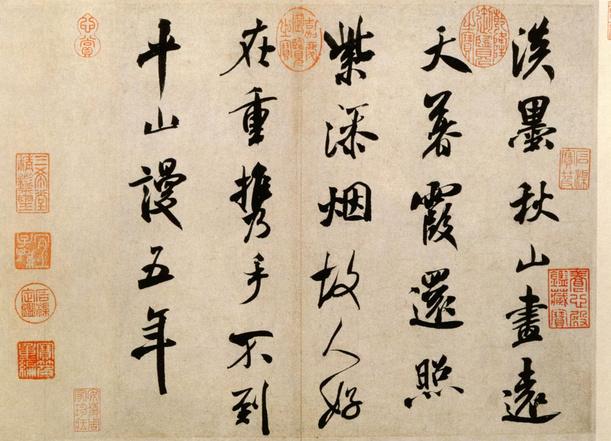

Ninth, observe the overall composition and layout. Compare the spacing between characters and between lines. Notice how each character is positioned.

Tenth, observe the signature and seal placement. Check whether their positions are appropriate.

The Importance of Thoughtful Study

From these “Ten Observations,” we can see that reading and copying calligraphy with careful thought and detailed study is absolutely necessary.

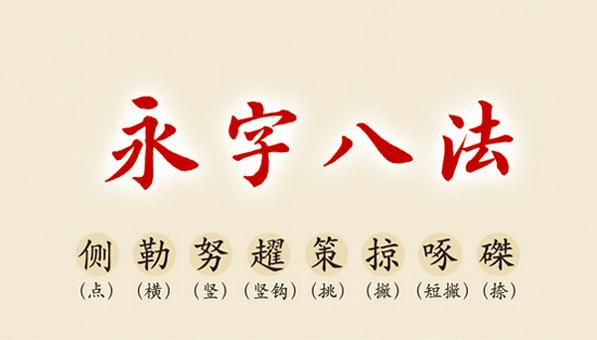

Everything in calligraphy comes down to brush control—the core skill is managing the brush tip’s movement in all directions: up, down, left, right, with varying pressure and speed. This also includes considerations of thick versus thin strokes, the strength of the structure, and whether the character achieves balance or falls short.

The Art of Character Composition

Chinese characters express meaning accurately and concisely. They emphasize what we might call “optimal arrangement” while also “considering the big picture” and paying attention to “yielding space.”

Depending on how components need to fit together, some parts are spread out while others are compact, some are long while others are short, some are loose while others are tight, some are thick while others are thin, some are large while others are small, some are wide while others are narrow, some are square while others are flat.

Cai Yong, a calligrapher from the Han Dynasty, explained this arrangement principle: “When writing characters, the upper part should cover the lower, and the lower should support the upper, so that their forms and momentum connect and reflect each other, never working against each other.”

Sun Guoting, a calligraphy theorist from the Tang Dynasty, said: “Those who observe should be precise, and those who imitate should aim for resemblance.”

Qi Ming’s Additional Note

Zhu Bi (Dwelling Stroke 驻笔): This is a brush technique in calligraphy where the pressure applied is less than a “pause” or “crouching tip”—meaning a “slight pause.” The brush touches the paper just enough before continuing to move. This technique is typically used at the beginning or end of vertical strokes, or at the curved parts of sweeping strokes.